Due Diligence in Dutch Gender Care

“In the Netherlands, we do it carefully.” That was the response from Amsterdam UMC1, Radboud UMC, UMCG, and Minister for Medical Care Pia Dijkstra2 to the Cass Review and the medical trans scandal in the United Kingdom. In this article, we explain that this is nonsense and that there CANNOT be due diligence in ‘gender-affirming’ care based on current worldwide studies.

The Clinical Psychologist of the Hospital

We spoke with a clinical psychologist from the gender clinic in one of the Dutch hospitals. We cut to the chase: “What is the percentage of trans regret?”

The expected answer followed: “That is a difficult question, and we don’t know exactly.”

We have been providing sex reassignment care in the Netherlands since 1987 and we do not know the regret percentage? The only question they should have investigated has not been: How are the patients faring after medicalization and surgery? A discussion followed in response to his avoidant and disturbing answer.

He repeated his answer and expanded on it: “We don’t know exactly, but the percentage is low, between 1-3%.”

The fact that he provided these numbers is no coincidence. But more remarkable is that he gave a double answer. On one hand, “we don’t know,” and on the other hand, it is “very low.” These do not mix well and are certainly not reassuring. The double answer suggests that trans regret floats somewhere between 1% and 3%, which is blatantly untrue. The true number lies extremely far above 3%.

Definitions and Language

There is no fixed and clear definition of what trans regret is exactly. Someone who has been castrated has a very different type of regret than someone who stops taking medication in time, let alone someone who halts their social transition. There is a distinction between irreversibility and reversibility, and the degree of suffering is vastly different.

The word “trans” itself also raises questions. What exactly is trans? Is it something you feel? Is it wearing clothing of the opposite sex? Is it taking hormones while keeping your organs intact? Or is it undergoing surgical procedures? Genderspeak is highly problematic because we do not know what it means. A clear definition is virtually impossible.

And let us not paint the world more beautiful than it is: Hitchcock based the main character Norman Bates in the movie Psycho on the ‘transgender’ Ed Gein. The wolf in Little Red Riding Hood is a grooming transvestite. Extreme examples, obviously, but a subgroup among transsexuals are the so-called autogynephiles (AGP), and it is known that they frequently exhibit sexually problematic or even criminal behavior. Creeps exist, hence the character of the trans wolf as a warning in Little Red Riding Hood, and AGP is a paraphilia. Norman, Ed, and the wolf are stereotypes of the most extreme form of AGP. The “no true Scotsman” argument does not hold: Every cross-dressing person is ‘transgender’ in Genderspeak, good and bad, including Norman, Ed and the Wolf, and milder creeps that love voyeurism, exhibitionism and humiliation of females or themselves as a sadomasochistic fetish.

27 Studies

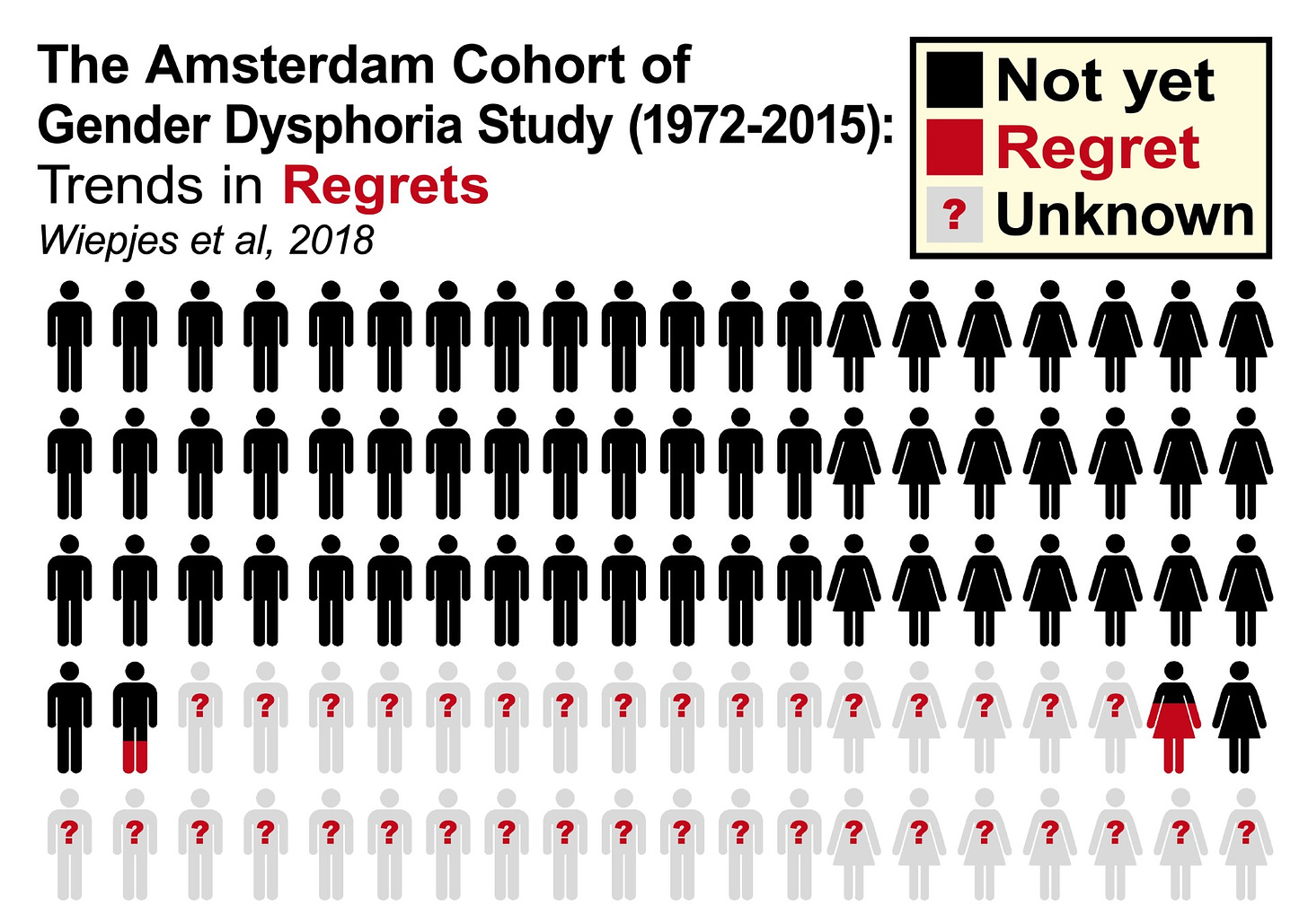

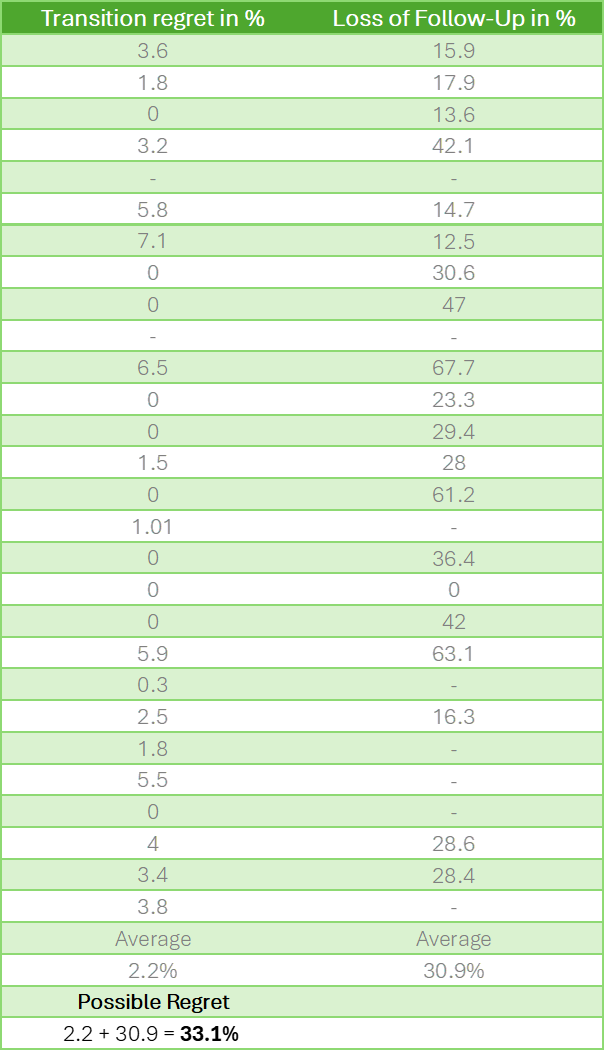

The mention of 1-3% did not surprise us. Often, the meta-study Regret after Gender-affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence3 is cited as the source stating that trans regret is “only 1-3%.” This meta-analysis is a summary of the most important studies on trans regret, and it is, therefore, appropriate to refer to it. However, these statistics have a significant problem: loss of follow-up bias. In other words, the missing participants. To reach a sound conclusion, there must be a correction for the measured results. This is often not achieved or avoided, making the conclusion essentially impossible.4

On Twitter, the diligent gender critic Michelle Alleva investigated the reality of trans regret linked to loss of follow-up.5 Alleva is a detransitioner herself. We placed the summary she made in a table below. The average trans regret is indeed “only 2.2%.” However, the average loss of follow-up is 30.9%. Why do participants refuse to take part in a follow-up study? Of course, it could be that they did not feel like it, or they emigrated, but we suspect there are much more painful reasons behind such a high dropout rate: shame and regret because you made a wrong choice and want to move on and especially not dwell on that disastrous decision. Or you committed suicide or died in some way, possibly because your body became unhealthy after the transition. We simply do not know. And precisely because we do not know, trans regret is not “only 2.2%,” but “possibly even 33.1%.” That is a significantly different number. Think about it for a while...

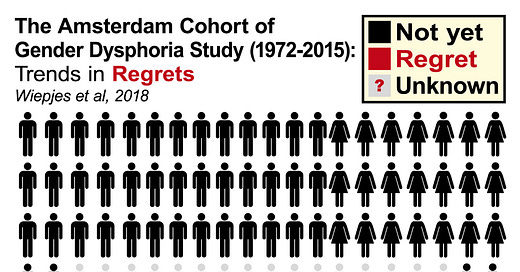

The study by Wiepjes (2018)6 is also often cited because it is the largest cohort study. And this study is even more important to us because it concerns the Dutch situation. In this study, the loss of follow-up is 36%. Even worse than the 27 studies in terms of noise factor.

The loss of follow-up also raises other questions. People who underwent a surgical transition are supposed to receive lifelong medication. How can these individuals disappear to such an extent? But here in the Netherlands, we do it carefully, according to the Dutch gender clinics and Minister Dijkstra. Do you still believe it?

In a conversation we had with the Irish psychotherapist Stella O’Malley, she made a beautiful analogy: “It’s like walking into a gym and asking, ‘Who likes to exercise?’ Everyone! The rest who don’t feel like it are at home.”

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”- Mark Twain/Benjamin Disraeli7

It has been too long since we had to calculate the standard deviation (σ) and correlation coefficient (r) during our studies, but anyone who has ever done this knows that the above data are downright bizarre and completely unusable as proof that regret is “only 2.2%.” The studies are abominably poor. In any science program, you should immediately stop with such study results. You would lose your job in any laboratory immediately.

But that is not the worst part: With a questionable outcome, you should add the noise to the possible risk and certainly not ignore it. That is fraud. The Wiepjes study mentions the loss of follow-up casually hidden in the long text, but not clearly in the conclusion. The clinical psychologist also avoided the noise in our conversation. This makes both the main study and the statement by the care specialist severely inaccurate. It is a statistical fraud with severe consequences for patients who trust these medical experts.

How Much Time Elapses Between Transition and Follow-up Research?

In addition to the shocking noise of 30.9% (or 36% in the Netherlands), there is another problem: trans regret often occurs only after an extended period. Many of the studies mentioned above measure during or shortly after the transition. Usually, patients are relieved shortly after the transition because they have finally completed the arduous process. This phenomenon is known as gender euphoria. But after the honeymoon period, life phases with turmoil appear, and all the choices made earlier turn out to be more complex. The average time for the occurrence of trans regret after transition is ten years.89 This makes all the aforementioned studies and the extreme noise even larger and more problematic.

Growing Criticism

A growing number of critical articles and studies are currently emerging at a rapid pace.10 1112 13 14 It is hard to keep up with the number of publications suddenly appearing around the downsides of the ‘gender-affirming’ care model. YouTube confessions about regret and physical complaints have recently surfaced en masse.15 It turns out that it is not as ideal for many. A notable study showed that 30% of people who ‘transitioned’ no longer take the necessary hormones after four years.16 The reasons for detransition can be broader than regret, for example, due to health complaints. In any case, it is a signal that confirms our concern about “possibly even 33.1%.”

Recently, the Cass Review was published, which aligns with this series of critical publications, and heralds the end phase of the gender-affirming model, although the Netherlands currently denies that there is anything wrong. The WPATH Files1718 are the highlight in the list of recent critical pieces, exposing a new low in WPATH’s behavior.19 Michael Shellenberger, whose organization published the document, calls it the Biggest Medical Scandal Ever.2021 Except for the Reformatorisch Dagblad (Reformed Daily, a Christian newspaper)22, the Dutch media completely ignored this publication.23

“Transitioning Does Not Make You Happy”

The conversation with the clinical psychologist went deeper than asking what percentage of people who transition experience trans regret. That question is incomplete. The real question should be whether people have an improved quality of life through sex reassignment procedures. And here comes the most remarkable statement from the clinical psychologist: “Transitioning does not make you happy.” We responded, “Huh? Then why do we do it?!” The clinical psychologist repeated this statement several times during our conversation. We were shocked to hear this admitted so openly. We still do not understand it.

A good insight into the ideological thought process in the Dutch gender clinics can be found in the podcast Gender: A Wider Lens, episode 66.24 One of the rare interviews where Annelou de Vries and Thomas Steensma are thoroughly questioned without prior preparation. De Vries is a child psychiatrist and head of the Amsterdam clinic, and Steensma is her colleague and psychologist. Together, they are the main proponents/defenders of the current policy in the Netherlands. In episode 69, interviewers Stella O’Malley and Sasha Ayad reflect on episode 66 and are still astonished by the answers they received.25

No Control Group

Since the medical and surgical procedures are accompanied by psychological care, it is impossible to distinguish why a patient has become happier. Is it because he or she has better understood themselves through psychotherapy? Or is it due to their body modification? This question is impossible to answer without a control group. Often, the argument is made that research with a control group (RCT) would be unethical, (also see footnote 11)26 2728 29 30 31 as also stated by Annelou de Vries from Amsterdam UMC.32 However, this is a gender activist standpoint and is debatable. The basis of Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) is that there is testing with a control group.33 If a care pathway does not meet EBM criteria, it is experimental. Isn’t it unethical to release an experimental form of care on a large group without first having a broad societal debate about what exactly EBM, control groups, and experimental care are? Or whether non-EBM care is wise for these individuals with mental distress? A group of patients that consists of children and vulnerable young people with a homosexual orientation and most of the time also mental comorbidities. The diagnostic overshadowing is clearly present and should no longer be denied in the gender-ideologically polluted clinics. This is also what Cass wrote in the Cass Review.

80% Desistance

Desistance means that your feelings change, and you feel comfortable with your birth sex again. Before the current increase in transgender care, a lot of research was done on this, and most young children outgrew their confusion without the need for transition. The percentages vary by study, but on average, this is significantly high: around 80%.34 For the current, newly emerging group of teenagers and adolescents with gender confusion, it is completely unknown how many will desist. This emphasizes the need not to take the individual’s feelings as the leading factor in care. Nevertheless, this is precisely what happens in the Netherlands, which increases the chance of even more regret after transition. Instead of taking a pause and reconsidering the care model, they scaled up from one clinic to three.

The Right Questions and the Sneaky Dentons Document

Because no research has been conducted with a control group, no solid statement can be made about the increase in life quality due to transition. We do not know, besides the enormous and often mentioned loss of follow-up, which suggests the opposite. Globally, research has not been adequately conducted. As a result, we are left with the half-hearted question of the trans regret percentage. However, this is only a superficial derivative of the essential questions:

Is there an improvement in the quality of life? (The straightforward answer from the clinical psychologist, “Transitioning does not make you happy,” suggests: No!)

How does mentally improved well-being compare to the clearly demonstrated large-scale physical problems that transsexuals face? (Such as 30% incontinence, 100% infertility, 30% orgasm problems, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, dementia, MS, repair surgeries, etc. The list is endless and very worrying.)

How does the success of the happy patient compare to the sad patients that have functioned worse afterwards? How do you balance this out?

But also, broader than just the individual:

How does the well-being of transsexuals compare to general societal peace?

How desirable is it that women have to compromise on their privacy, use of toilets, sports, and prison conditions?

This issue goes far beyond the care pathway and calls for an intensive and broad public debate in which the sociologist, the criminologist, the women’s rights expert, and the cultural philosopher deserve as much voice as the gender team. Through the Denton’s Document,35 gender care has deliberately avoided this debate: that is reprehensible. They pretend that this is solely a medical issue and not a cultural one. The writer Graham Linehan has written two revealing articles about this hidden side of gender activist care.3637 In terms of ethics, transparency, and care, it is worth pausing to consider what exactly has happened here. Politics permeates the care pathway.

Dr Az Hakeem and Unread Gender Critical Literature

The argument about asking the right question does not come from us. Professor Az Hakeem worked at the Tavistock Clinic in the United Kingdom for twelve years. This clinic is comparable to the gender clinic for young people at Amsterdam UMC. Hakeem worked there from 1999 to 2011, long before the number of patients with gender dysphoria exploded, which began around 2012 and rose sharply around 2016. The British clinic is often criticized for increasingly neglected its duties, as accurately described by Hannah Barnes in her book Time to Think.3839 Hakeem plays a prominent role in this book. During the time he worked at the Tavistock clinic Hakeem, together with whistleblower Sue Evans, had already realized the gender-affirming care model was fundamentally careless in its core philosophy. From the beginning, things went wrong. The model used at the time was directly adopted from the Netherlands. In other words, things went wrong in the Netherlands from the start as well.

Hakeem currently runs the only post-operative psychotherapy program in the world for transsexuals with psychological problems. Hakeem wrote the book Detrans: When Transition is Not the Solution40 in which he outlines his insights: according to his experience, about 30% of transsexuals regret the surgery. He also describes in detail how, with the help of group therapy, wrong choices by trans patients can be prevented as much as possible. He also presents a measurement method in the book to measure the persistence of gender dysphoria as accurately as possible. This form of group therapy and the persistence measurement method are not applied in the Netherlands.

The clinical psychologist we spoke to had not read Hakeem’s book. We got the impression that he did not even know the name Az Hakeem. He had not read Hannah Barnes’ book either. Nor had he read any of the books by Debra Soh,41 Abigail Shrier,42 Kathleen Stock,43 Helen Joyce,44 or the WPATH Files. These are roughly all the critical books on this subject, each a bestseller with high review ratings in English-language quality media. Publications from Dutch hospitals are often accompanied by a source list. Two major publications were made in 2023 and 2024: Mijn Gender Wiens Zorg,45 (My Gender, Whose Concern?) published by the Radboud Hospital in collaboration with ZonMW, and Evaluatie van de kwaliteitsstandaard Transgenderzorg - somatisch,46 (Evaluation of the Quality Standard of Bodily Transgender Care) published by the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists. In both publications, these books are absent from the source lists. The fact that these books, as well as the WPATH Files, are completely ignored by the Dutch experts, does not strike us as diligent.

These philosophical books delve deeply into sociology, current society, ROGD (Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria), youth culture, youth issues, Transhausen by proxy, internalized homophobia, the role of newspeak in truth-finding, and the ideological agenda of gender activist organizations. This is not simply a medical problem but primarily a cultural problem. And the latter cannot be investigated through healthcare methods; for that, you need historians, philosophers, sociologists, mass psychologists, investigative journalists, and semanticists. And, judging by the source list, these are not consulted. Gender care often claims to work in a multidisciplinary manner, but a medical monoculture has emerged that is blind to culture and society and any form of criticism. They are perfect, trust them. No.

Cognitive Dissonant Denial

The last problem I want to mention is the cognitive dissonance in relation to well-being after a ‘gender-affirming’ care trajectory. If you get an ugly tattoo, it takes time and courage to admit that it is a failure. It is an extra step to then have it removed by laser. The cognitive dissonance with sex organ and breast amputations can be much greater than with an innocent tattoo. An amputation cannot be undone. In the United States, leading gender surgeons like Marci Bowers euphemistically speak of a “gender journey,” thereby despicably placing the full responsibility on the patient: It is your journey, your adventure. For many, admitting they made a wrong choice is simply not an option because it would mean their ‘journey’ ends like in the movie Thelma and Louise: Over the cliff.

I am aware of the sensitivity of referring to Valentijn de Hingh, but he has said the following in an interview with Elle magazine,47 and I am merely repeating what he said. I leave it to you, the reader, to interpret his response yourself, but I also request you to keep your judgment to yourself and not express it loudly. This could harm Valentijn after all. For English readers: Valentijn is the poster kid of ‘gender affirming care’ in the Netherlands. Comparable to Jazz Jennings and I am Leo. You all know how successful Jazz Jennings’ process has been. Leo is out of public sight. Valentijn is still a public figure. Let us hear what he has to say about himself.

What do you feel the most regret about?

‘Oof, that’s difficult.’ She hesitates and stutters a bit. ‘Well, I… I wouldn’t call it regret, but there is something I find regretful. If I look at my own identity and how it has developed over the past few years... I always thought that in your transition you go from one box to the other, to man or woman, one of the two. That you then arrive somewhere. But it never really felt that way for me. I started, of course, when I was very young. Already at five years old. The only options I thought I had available were man or woman. I definitely knew I wasn’t a man, but what was I then? I mostly just felt like myself. Still, I went one hundred percent for being a woman. Only after my transition did I realize that. I am very comfortable with my body, and you can certainly call me a woman and refer to me with ‘she’ and ‘her,’ but after my transition, I realized that it can also be different. You don’t necessarily have to fit into one of those two boxes. There is also something in between. I wish I had known that earlier.’

Conclusion

In our article we have tried to show that the question, “what is the percentage of regret” cannot be answered because the studies that exist do not include control groups48. In some ways however, even this proceeds from a false hypothesis. Instead of asking ‘how much regret?’, the real question should be: “how did the well-being of the group that underwent GAC (gender affirming care) compare to the group who received only psychotherapy?” Unfortunately, that has never been researched.

The well-being of transsexuals remains very unclear. In every aspect, we repeatedly encounter more questions than answers, which seriously concerns us. What is clear, in any case, is that this kind of care, no matter how well-intentioned, cannot be conducted carefully. The lack of diligence is so significant that we seriously question whether we should allow this in its current form as a society. Or rather, we do not question it: No, we should no longer want this.

'This article was originally in Dutch published by Voorzij.' Transspijt is mogelijk 33%

Genspect publishes a variety of authors with different perspectives. Any opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect Genspect’s official position. For more on Genspect, visit our FAQs.

“View the original version of this article in Dutch: Transspijt is mogelijk 33%” - transspijt is the word translated

the Dutch word spijt could be literally translated as “regret” as in “het spijt me” - “I regret” or “I am sorry”

But the deeper feeling of the Dutch is to have a mix of sorrow, regret, and … grieving.

One regrets a tattoo, or buying a Tesla.

One grieves for a death.

Granted Trans use “deadname” the idea grief is apt.

The Dutch spijt and English spite are not related though pronounced almost identically.

The title of this substack is misleading and unfortunate because, as the essay shows, “regret” is too simplistic a concept to convey the questions we should be asking.