It's often assumed that being trans is somehow very similar to being gay. But the truth is a little more complex – and we'd like to show you how.

As a gay man, I grew up with a certain idea of the gay community. Sometimes, this idea was a bit skewed: "talking heads" on TV tended to be gay men, rather than lesbians; there was also a skew towards the young, and the urban. Representatives of the gay community weren't often quite as diverse as they might have been: the retired lesbian living in Devon or Northern Ontario or Kansas was less likely to make it onto the screen than, say, the young gay man living in London or Toronto or San Francisco.

Whether or not the phrase "LGBT" was used, there was usually (though not always) some idea that we had common cause with trans people, at least to some extent. Even if it wasn't stated overtly, we were all sexual minorities; and for some time, this was unproblematic for most of us. But this has now become very controversial. With the growth in the number of people identifying as trans, many LGB people see the need for a distinct movement for same-sex attracted people.

The result? We're all thinking more about what it means to be gay, and what it means to be trans. And that's something which deserves its own analysis.

In general, we take other people’s internal experiences at face value. If you say you’re hungry, you'll probably be believed; likewise, if you say that you’re gay, or if you say that you’re trans. We take one another at face value, because we don’t accuse one another of dissembling without good reason, and certainly not of lying.

So, it is probably to be expected that many people believe that there is a fundamental similarity between sexuality and gender identity. Both seem to be internally observed qualities, qualities that we can only know ourselves. ‘After all,’ you might think: ‘could all of those LGBT organisations be wrong, when they include the T alongside the LGB? There must be something in it.’ And no-one wants to repeat the errors of the past, when parliaments, schools, religious congregations and medical establishments collectively failed to extend basic human dignities to homosexuals.

But assuming that ‘being trans is like being gay’ is a simplistic viewpoint. There are many distinctions to be made between gender identity and sexuality – and these distinctions are critical to those of us who work with parents of gender-questioning kids, with detransitioners, and with those who have transitioned yet feel ambivalent, or even negative, about the healthcare they received. Lumping together these two quite different concepts can be misleading, and indeed have unforeseen consequences.

To create a more developed conversation about trans issues, Genspect is offering you a step-by-step guide to understanding why it's important to deal with gender and sexuality as separate notions. Read through at your leisure, or click to jump down to the arguments which interest you:

1. There have always been gay people. There haven’t always been trans people.

2. Gay people exist all across the world. Trans people don’t.

3. Homosexuality is seen across the animal kingdom. Transgenderism isn’t.

4: Being gay is empirically verifiable. Being trans is not.

5. Being gay never requires medicalisation. Being trans usually does.

6. Being gay does not typically have comorbidities. Being trans typically does.

7. Being gay is not socially influenced. Being trans is.

8. Being gay does not require others to change their behaviour. Being trans does.

9. Being gay is not premised on social stereotypes. Being trans often is.

1. There have always been gay people. There haven’t always been trans people.

Gender identity theory is the notion that what makes you a woman, or a man, or indeed something else, is an internal identity, to be taken on trust. But this notion is entirely modern. Historical titbits offered up as proof that trans people have existed throughout time typically fray apart: claims that headstrong and courageous women of history were in fact non-binary turn out to be nothing more than misogynistic assumptions that females aren’t, or perhaps even shouldn’t be, headstrong and courageous. This is hardly progressive thought.

Many young people today seem to experience profound distress at being ‘misgendered’ by those who do not accept their gender identities. This, too, is entirely modern: there is no evidence that historic cultures accommodated today’s notion of self-identification of gender. In fact, past figures who bucked the trends of contemporary masculinity and femininity were notable because their status as men and women was not in debate. It was not something they sought to dispute with their contemporaries.

Sexuality, on the other hand, is as old as the hills. Homosexuality warrants mention in the Bible – albeit unflattering mention – and other ancient religious texts besides. Gender identity does not. Historic figures such as Alexander the Great are believed, with good cause, to have had same-sex relationships; the argument that such figures have ‘trans’ equivalents rests on conjecture, defying rather than drawing from the historical record.

2. Gay people exist all across the world. Trans people don’t.

Different cultures have different responses to same-sex attraction – sometimes, as in countries like Saudi Arabia, with devastating consequences for gay and bisexual people. This naturally results in different national self-images. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad proudly declared that Iran has no gay people: and it is hardly surprising that Iranian gays would be keeping their sexuality on the downlow, given the punishments which would otherwise await them. So we can expect estimations of the incidence of homosexuality to vary across borders.

Yet all countries and cultures make mention of sexuality in one way or another. Whether it’s ticker-tape pride, general acceptance, grudging tolerance, or blanket criminalisation, jurisdictions legislate on matters of sexuality. Gay sex is, or is not, legal; ditto, gay marriage, and the adoption of kids by gay couples. These matters may be adjudicated in remarkably different ways – but adjudicated they are, from Uruguay and Belgium to China and Mozambique.

The inclusion of gender identity in legislation and educational materials, on the other hand, is an inherently ‘WEIRD’ world phenomenon (where ‘WEIRD’ stands for Western, educated, industrialised, rich, developed). While countries in Africa and Asia may have much to say regarding sexuality – whether positive or negative – trans rarely gets a look in. It is predominantly in Western Europe and (especially) English-speaking North America that gender identity receives as much attention in law and regulation as sexuality. That’s why languages typically have their own native vocabulary to describe homosexuality, yet import terms from English to describe transgender identities.

The few seeming exceptions to this rule do not exactly corroborate the current Western idea of innate gender identity. While the Fa’afafine of Samoa have been asserted as evidence of a ‘third gender’, the (male) Fa’afafine are in no doubt that they are male. And while the Hijra of India are usually described as believing themselves to be neither male nor female, they are ultimately a socially marginalised group of transvestic eunuchs – far from an uplifting tale of gender diversity in which we might find much to learn. The binary nature of sex is not a Western construct, but a biological reality innate to our species; what may seem superficially to be evidence of the cross-cultural nature of gender identity is in fact rather different, and in a few cases rather more sinister.

3. Homosexuality is seen across the animal kingdom. Transgenderism isn’t.

As a National Geographic article rather musically puts it:

Birds do it, bees do it, even educated fleas do it. So go the lyrics penned by U.S. songwriter Cole Porter.

Porter, who first hit it big in the 1920s, wouldn’t risk parading his homosexuality in public. In his day “the birds and the bees” generally meant only one thing – sex between a male and female.

But, actually, some same-sex birds do do it. So do beetles, sheep, fruit bats, dolphins, and orangutans. Zoologists are discovering that homosexual and bisexual activity is not unknown within the animal kingdom.

To some gay people, this might seem a little off-colour. ‘So what?’ they might be forgiven for thinking. ‘What if there weren’t gay dolphins? It has nothing to do with loving, adult, homosexual relationships.’ Yet, were it not for the existence of homosexuality in the animal kingdom, it could be argued that human homosexuality were purely a psychological phenomenon. While we are still unclear on the precise balance between nature and nurture, it is evident that there is at least some natural, biological component to homosexuality.

The same is not true of transgenderism. It cannot, by definition, occur in non-humans, premised as it is on the very things that make us human. On clothing and styling, not in play for any other species. On language – whether names and pronouns, or the means by which people describe their gender identities – again, not in play outside of Homo Sapiens. And on our deeply human obsession with considering who we are; how we relate to the world; how we are seen, and not seen. While it may seem odd to have to delve into the realm of the fruit bat and the orangutan to investigate human sexuality, there is a real point to be made here. Transgenderism, so philosophical a concept, rests its existence on human mental constructs which are not required per se for any understanding of same-sex relationships.

The original gay rights movement had the striking slogan, ‘Born this way’. The argument was simple: gay people were communicating to the wider world their own inescapably biological instincts, in the face of ideological opponents who believed they were making a choice to defy nature. The slogan worked. Then, some decades later, ‘Born in the wrong body’ became the rallying call of the trans rights movement. Yet no-one can be born in the wrong body: just like the orangutans, we have the biology dealt to us in utero, whether we like it or not.

4. Being gay is empirically verifiable. Being trans is not.

Same-sex attraction, like all sexual attraction, has physical consequences. If you see an image of a person you find sexually attractive, your body responds: your heart-rate quickens, for example. (And, of course, the male body has a more immediate way of demonstrating sexual excitement.) This means that same-sex attraction is verifiable, in the empirical sense. If you claim to be gay and are lying, you could be proven a liar – at least theoretically.

Being trans, on the other hand, has no biochemical processes attached to it, other than the biochemical changes which are made to the body by medicalisation. In other words, it’s not something we can test. While this point may seem academic, it is of great philosophical relevance: coming out as gay is making a claim of an internal reality which goes beyond the cognitive or the intellectual. When young people come out as trans, they are describing how they feel within society, and how they might wish to change that feeling by presenting differently. They are not describing impulses of the body that can be analytically studied.

As Arty Morty puts it: ‘Trans is not a thing you are, it’s a thing you do.’ Some might find this a cruel idea to level at a young person who is gender-questioning, as it could be seen to deny an internal reality. Yet it is not denying an internal reality so much as qualifying it, and differentiating it from an altogether different type of experience. While adolescents who realise they are same-sex attracted may feel as though they have decisions to make, especially around coming out, there is no ambiguity about the same-sex attraction itself: it’s right there, in the pumping of the blood, like it or not. Agonising about ‘whether or not I’m trans’, on the other hand, is a worryingly common phenomenon, only serving to demonstrate the importance of gender identity’s unverifiable nature.

5. Being gay never requires medicalisation. Being trans usually does.

This may be an obvious point, but it bears mentioning: sex reassignment surgery, recently rebranded as the much less scalpel-implying ‘gender-affirming care’, is a development so new that we simply don’t have long-range data on physical, psychological and social outcomes over the course of a whole lifetime. Trans people are dependent on clinicians to guide them through a very complicated process which can take a serious toll on the mind and body; and many detransitioners do not believe, in hindsight, that the guidance they received was adequate.

It is true to say that there are young people who see themselves as trans and do not wish to undertake medicalisation. But these are in the minority. More often than not, kids who are questioning their gender have specific ‘transition goals’, which are bodily in nature. Often, young people who identify as trans, or as non-binary, can devote a colossal part of their time to their appearance, and how they would like it to change. These changes can be very major, involving hormones and surgical interventions. They are not to be undertaken lightly.

On the other hand, homosexuality, in its own right, never requires a visit to the doctor. To live as a homosexual in society, no prescription is needed; no medical appointments need to be made. While young LGB people are certainly more likely to struggle with mental health issues, and may seek medical help for these, this is not, in and of itself, a form of medicalisation. To live authentically as a homosexual, you accept your own body, and its biochemical responses to the stimuli around it. To live authentically as a trans person, you are often doing the opposite: seeking to change your body in a way which will leave you dependent on doctors, endocrinologists and pharmaceutical companies for the rest of your life, with all the financial and other burdens that implies.

6. Being gay does not typically have comorbidities. Being trans typically does.

Coming out as gay can be difficult. Bullying is rife; and the ensuing negative feelings can sometimes be visited upon the self, through depression, anxiety and even self-harm. However, these mental health difficulties, often termed ‘comorbidities’, are very often reflexes of the absence of societal acceptance, whether from friends, peers, family members, or indeed the self. In other words, they are responses to a social context.

Comorbidities work entirely differently among trans people, seeming to suggest that there is something quite distinct going on. We know, for example, that there are profound connections between transgenderism and autism, connections we have barely begun to understand; there are also stark statistical correlations with other mental health conditions, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and disordered eating. (For more on these comorbidities, check out the relevant page on Genspect's sister website, Stats For Gender.) Often, parents of gender-questioning adolescents report that these comorbidities long predate their kids’ transgender identities.

The many detransitioners Genspect works with often attribute their previous fixation on gender to such comorbidities. With the benefit of hindsight, some come to see that hyper-ruminative thought patterns contributed to their desire to transition, convincing them that medicalisation was the only answer to their distress. There is scant evidence of any equivalent phenomenon among people who were once homosexual, but no longer are. While such individuals exist, they are rare; rarer yet is the attribution of same-sex attraction to a pre-existing mental health condition. In other words, when it comes to comorbidities and mental health, there seem to be unexamined links with transgender ideation that are simply absent when it comes to homosexuality.

7. Being gay is not socially influenced. Being trans is.

Gay people appear in all walks of life: all socioeconomic classes; all demographics. Yet the distribution of transgender identities is strikingly different. In the last ten years, there has been a surge of young, predominantly female adolescents identifying as trans. There is no equivalent surge in, say, middle-aged or elderly women.

One argument is that this relates to the growth of acceptance of trans people. In some ways, this is a remarkably arrogant position: we, uniquely, in the developed, twenty-first century West, are the only human beings who have ever got this right, and everyone else throughout geography and history has been so poisonously transphobic that millennia’s worth of trans people have been confined to the closet. But even if the inherent arrogance of this position is overlooked, the explanation does not hold. There has certainly been something of an increase in acceptance of homosexuality; and while it may have resulted in a few more gay and bisexual people feeling confident enough to come out, it has hardly caused the stratospheric demographic surge we observe among trans-identifying youth. If it had, there would barely be any heterosexuals left on the planet.

Social influence, or even contagion, is known to be at its most rife among teenage girls. It is among teenage girls that eating disorders spread with the greatest virulence, so much so that they are often separated from one another during in-patient care. The little research which has been undertaken corroborates this: trans-identified females are more often than not part of friendship groups in which very nearly all of their peers also have a gender identity at odds with their biological sex. It is clear that transgenderism is socially mediated, causing it to flourish in some social circles, and to be virtually absent from others.

8. Being gay does not require others to change their behaviour. Being trans does.

When a teenager comes out as trans, it’s often with great fanfare. This may be because a flurry of changes accompany the revelation of a transgender identity: the young person might wish to be known by a different name, or even be referred to by different pronouns. These changes require the active participation of those around them, whether family members, teachers, friends, or fellow students. In turn, this may provide a sense that some positive change in their relationships with others has been accomplished, and alleviate normal teenage feelings of self-doubt, stagnation and self-loathing. In extremis, these changes can be so radical that they demand an overhaul of the normal grammatical paradigm of English, using 'they' to refer to a specific, named individual – even though the English language has no history of doing so.

Coming out as gay, on the other hand, requires no such modification of behaviour in other people. True, you might have a rather dull romantic life if no-one recognises the validity of your homosexuality: but there are no concomitant demands placed on everyone else, simply as a result of being gay. No names or pronouns change. No-one uses a different bathroom, or needs to order a new copy of an official document such as a passport or driving licence. When you think about it, transgenderism depends entirely on such behavioural changes to exist: at its heart, it is a social phenomenon, only making sense at a conceptual level if it enjoys the recognition of other people.

And these behavioural changes are not neutral, in terms of their impact on others. Many of the parents we represent describe to us how difficult and traumatic it can be when their children ask them to upend an entire vocabulary, effectively re-learning how to speak – and even think – about their own offspring. After fifteen or twenty years of calling someone your daughter, it is no mean feat to start saying ‘my son’. The rewriting of history is unique to the transgender identity, based as it is on the idea that something has been discovered – something which was always there, but never seen. No equivalent shift in behaviour is required when an adolescent comes out as gay.

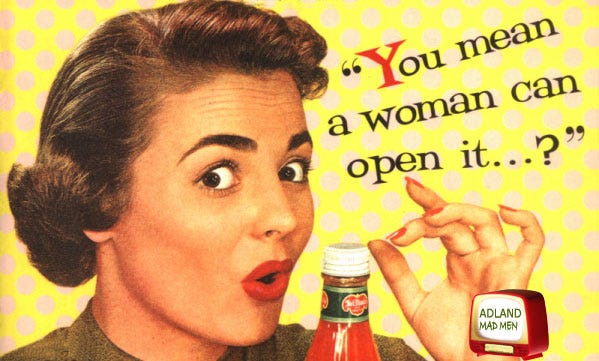

9. Being gay is not premised on social stereotypes. Being trans often is.

Regardless of your sexual orientation, you can be someone who conforms to social stereotypes, or someone who bucks them. There are lesbians who are ‘butch’, preferring activities that are classically seen as ‘more male’, and perhaps dressing in a more conventionally masculine way, too. But there are also lesbians who do not present to the world in a way which is any different from the average woman. These stereotypes, whether expressed through activity, hairstyle, clothing, styling, or other characteristics and mannerisms, can intersect with homosexuality; but homosexuality itself is not premised on them.

When young people come out as trans, they very frequently make reference to such social norms when explaining why they feel the way they do. These norms, not exclusive to those who identify as trans, become justifications of the transgender identity itself. I first knew I was a girl when I realised I didn’t like sport. I first realised I was a boy when I realised I didn’t like makeup. In practice, adolescents who see themselves as trans are fathoming a new identity according to these social mores, even though such mores vary across cultures and throughout history.

Many older gay people find this sinister – as do, for example, women’s rights advocates. Much of the latter half of the twentieth century was spent debunking ideas which were seen as regressive, such as the notion that women should be sweet and caring, and men should be bold and decisive. For many, it is unsettling to witness the younger generation re-establish what it is to be male and female on the basis of outdated sex stereotypes. An alternative to this is a more expansive vision of biological sex, one in which there is no right way to be a woman or a man. Sexuality simply doesn’t implicate social stereotypes in the same way: they may be relevant, but they are not the means by which the sexuality is itself divined.

This list may not be exhaustive, but it certainly demonstrates how much goes overlooked when gender identity and sexuality are elided, as happens so commonly in today’s culture. For detransitioners, this is no small point: one study found that nearly a quarter of detransitioned people believed that homophobia or difficulty accepting themselves as lesbian, gay, or bisexual led them, in part, to transition. A further study of detransitioners and desisters found that over half expressed a psychological need for learning to cope with internalized homophobia. The conflation of gender identity and sexuality can be actively dangerous, leading vulnerable young people to make decisions they might later come to regret.

So no, trans is not the new gay. LGB people deserve respect; trans people, too. Blurring the lines between these different concepts, while it may feel like the easiest option, is not necessarily the right way to demonstrate such respect. In fact, you may be doing quite the opposite.