The Alchemist and the Algorithm

How the algorithm shapes ASD, digital natives, and love

By now, there is a general recognition that social media is not good for young people. The negative impacts have been well documented. Heavy social media use significantly increases depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior risks in all teens but particularly in teenage girls, who are vulnerable during early adolescence (ages 11-13). At the same time, boys suffer too, but in a different way. They are less likely than girls to report social media hurting their mental health or confidence, but they face unique challenges like exposure to harmful content, promoting violence, or substance abuse. Social media is also closely associated with trans identification.

The effects are so worrying that former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, issued a report titled ‘Social Media and Youth Mental Health’ in 2023 and recommended that Congress pass an act placing a surgeon general’s warning label on social media platforms the following year. And yet these outward, observable effects fall short of capturing or describing the profound changes wrought to the fabric of our personalities. It is not just what we encounter online, but the way our expectations, aspirations, and perceptions are being reshaped by an invisible hand: the algorithm.

The Alchemist and the Algorithm

I met the man I came to think of as ‘the alchemist’ in the mid-1990s at the Hub Club, a monthly gathering for designers and developers involved in what was then called new media. The ‘club’ was a place to showcase projects, look for work, and debate where things were headed. It was a time of mostly unbounded optimism about the promise of connection and unleashing human creativity on a global scale. Twelve years before the iPhone, in the days of dial-up modems, we were just on the cusp of ‘the information revolution,’ and the question that preoccupied us was how to connect users with the unprecedented amounts of content. Though I didn’t know it at the time, it was a portentous meeting.

The Web ca. 1995

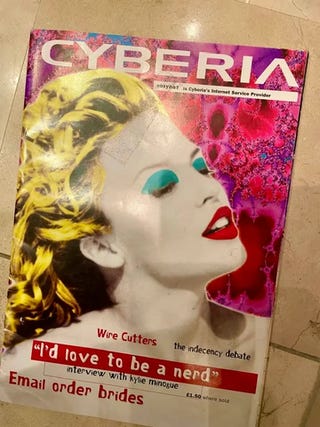

Although no record of The Hub Club exists, this clip from a documentary about Cyberia, an Internet Café on Whitfield Street in London, captures the mood of creativity and optimism (and embarrassing naivety) that surrounded the web in the years before algorithmic curation.

After one particular meeting, as we sat in the pub listening to a 20-something designer named ‘Dave’ explain at length how we would all eventually exist as avatars online and gather in ‘virtual nightclubs, ’ the older man sitting next to me snorted derisively. He confided, ‘All that we saw tonight, the games and that, it’s all rubbish. It’s the code that matters.’ His opinion was seriously at odds with the majority of the Hub Club’s designer-heavy crowd. They regarded the challenge as one of interface design, what web pages looked like, how fast they loaded, and whether they were intuitive to use. He looked out of place, and his comment was curmudgeonly, but there was something about him that piqued my interest.

He was a ‘type’ I knew well from my days in the tech industry: eccentric, not adept with irony; assumed everyone knew DoS, and if they didn’t, what was wrong with them? Today, he would probably be labeled ‘autistic,’ but back then, he was simply a nerd. When I asked him what he meant, he launched into a very technical explanation of algorithms (most of which was over my head), culminating in the revelation of his pet project: ‘an algorithm for love.’

That got my attention. ‘Really!?’

‘Of course,’

He continued…

‘Say you have two users, Mary and John, who complete a 50-question survey capturing data on age, location, interests, values, and deal-breakers (e.g., smoking).’ Each response is scored on a scale of 1-5. We compute compatibility using a weighted scoring system, where critical factors, such as ‘wants kids,’ carry a higher weight (0.8), and less critical ones, like ‘likes sci-fi,’ have a lower weight (0.2). If Mary and John both strongly agree on wanting kids (score = 5) and enjoy hiking (score = 4), their compatibility score, normalized to 100, reaches approximately 85. Based on historical user patterns, predictive analytics suggest a 75% chance of a second date, a 20% probability of a one-night stand (dependent on their casual dating preferences and physical attraction metrics), and a 40% likelihood of a long-term relationship, assuming alignment on unmodeled interpersonal factors.’

He looked pleased with himself. ‘I’ve almost finished it!’

‘Poor, poor man,’ I thought. Did he seriously think he could turn data into love? I felt sorry for him! And yet, today, I wonder if I was wrong to scoff.

Today, the alchemist’s ‘code’ is a reality. The algorithm drives everything about the internet, from search engines to social media. It anticipates what we want before we know ourselves. It mediates our friendships, our social circles, and, as for love, who doesn’t know a couple who met on a dating app? It sounds like a roaring success. Yet the woes of young people tell a different story: not one of love, but of loneliness and a relentless striving for outcomes, cycles of curation, followers, tweaking profiles, ‘body goals,’ purchases, ratings, and consumer reviews.

Did the alchemist crack the algorithm, or is the algorithm cracking us?

What is The Algorithm, and Where Did it Come From?

In an era of compulsive connection, when we are seldom without our phones, we take our desire to connect for granted. It is hard to imagine the cumbersome early days of the World Wide Web: dial-up modems, navigation modeled on newspapers, crude pop-up ads, and GIFs. Despite the optimistic build-and-they-will-come attitude of early web designers, except for pornography, users seldom showed up without extensive offline marketing campaigns. Developers like the alchemist were initially hired by search engines (AltaVista and later Google) to analyze user behavior in an effort to help connect people with the information they were looking for, and more lucratively, to connect them with what companies wanted them to find. By analyzing what users searched for and clicked on, how long they spent on each page, and where they spent their time, developers were able to make predictions that would drive e-commerce, target political ads and news stories, and, just as the alchemist predicted, match potential romantic partners.

The algorithm, as we refer to it today, is the complex set of rules and calculations used by social platforms, like X, YouTube, or Tinder, to curate and rank content for users. It analyzes user behavior, preferences, and engagement to prioritize posts, videos, or ads, shaping what appears in feeds or search results — just as the alchemist predicted. It is not a singular calculation—it’s not quite SkyNet yet. Each platform’s algorithm is unique, often opaque, and evolved to optimize user retention and platform goals. Thanks to the transformation of data collection (those permissions buried in the fine print of user agreements), ‘optimization’ of your content is nearly impossible to escape. Innocently refer to ‘Shark Week’ in the presence of your phone, and you’ll find yourself assailed with reels about sharks, shark attacks, and lionfish extermination. Mention an upcoming trip and you’ll receive ads for travel clothes and theft-proof bags. Every pause, every click, every reel, every meme helps the algorithm to craft an online world just for you. It might not be the world you were looking for, and sometimes it feels intrusive, but it is oddly compelling, as if it knows us better than we know ourselves. But the truth is much darker — the algorithm doesn’t know us, so it changes us.

The Medium is the Message

In his 1964 book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Marshall McLuhan argued that ‘the medium is the message.’ He meant that a medium’s form, not its content, shapes how messages are perceived and influences societal behavior in turn. Writing in the 1960s, when television was the new ‘disruptive technology’, he compared its visual immediacy to print’s linearity, speculating about how it might impact human interaction and culture. He was correct. Later studies of television showed that what viewers watched, such as true crime shows, influenced their perceptions, leading them to overestimate or underestimate real-world phenomena, like crime rates, in line with what they had watched. Now, imagine if television shaped viewers' worldviews through passive immersion, as McLuhan described. Imagine how the algorithm-driven internet manipulates emotions through active engagement and reinforcement.

How does online communication impact human relationships? Some ways are obvious. The Internet allows us to sidestep space and time. We can stay in touch with faraway friends and form new relationships across geographical barriers and time zones. These new connections are strangely intimate: a GoFundMe campaign raises tens of thousands of dollars from strangers to help people they don’t know pay their rent or cover medical expenses. A viral post on X can make or break a reputation, while eccentricity or special interests shared on platforms like Reddit and Discord bring people together in a niche community for the most esoteric of reasons. Some of these are innocent — think Project for Awesome, which raises funds for charities, while some, like r/incels (now banned) and ‘underaged dating’ (also banned), were downright sinister, but none of them could exist in the same way without the internet. Social media and influencer culture on platforms like Instagram and TikTok encourage comparison and self-curating. But the most profound effects are more insidious.

Digital Natives

For those born into the algorithm-driven world, the impact of digital media extends beyond what it gives them access to. Unlike their parents, who adapted to digital life, digital natives have never known a world without curated feeds, instant likes, and algorithmic matchmaking. Their relationships, from friendships to romance, are mediated by platforms that prioritize engagement over authenticity. A teenager scrolling through Instagram may feel inadequate comparing themselves to an influencer’s polished life, unaware that the algorithm has curated that feed to maximize their time spent on the app. A young adult on Tinder swipes through profiles, reducing potential partners to a checklist of traits — just as the alchemist’s algorithm reduced Mary and John to data points. It leads them down a path of preconceived but invisible choices, ultimately leading them toward some outcome. Whether that outcome is good or bad matters less than the fact of its existence. People like the alchemist have shaped these choices.

Algorithmic Social Dynamics

There is a phenomenon known as the ‘Gen Z Stare,’ which describes the seeming inability of people in Generation Z to pick up on social cues. Instead of making eye contact or giving the cues of active listening, they gaze off into the distance as if they were somewhere else. One of the explanations given for this now common behavior, especially in young men, is excessive screen time. Child’s play that would have taken place face-to-face in another era is now filtered through a screen via text or video chat. The emotions are there. The joys and woes of growing up are just as strong as ever — maybe stronger given how much emphasis we give them — but the real-life social interplay between young people and, more worryingly, between generations no longer exists in the way that it did. To put it bluntly, we are all alchemists now. Instead of learning to relate to people through the rich, embodied trial and error of in-person social interactions, Gen Z’s natural capacities for understanding others have been suppressed and molded into a very black-and-white, autistic-like way of being.

It has long been known that non-autistic individuals deprived of face-to-face social interaction in childhood can display autistic-like traits, such as poor eye contact or repetitive behaviors, as seen in Romanian orphan studies where 10-16% of children showed quasi-autistic patterns that were distinct from autism spectrum disorder but similar in appearance (Rutter et al., 1999; Kreppner et al., 2001). Could we be seeing something similar with Gen Z? Could algorithms, designed by people like the alchemist, be pushing young people into hyper-specialized, echo-chambered content, fostering niche online communities that encourage intense, autistic-like focus (Anderson & Jiang, 2018)?

The Link with Gender

A staggering 11% (some estimates are even higher) of trans-identified individuals are diagnosed with autism, a rate significantly higher than the general population’s 1-2% autism prevalence, with studies indicating trans-identified people are 3 to 6 times more likely to have autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Warrier et al., 2020). This overlap may be driven by the pronounced ‘black-and-white’ thinking often seen in autism, where rigid, binary cognitive patterns may lead to a more intense and focused exploration of gender identity, potentially amplified by difficulties in understanding stereotypes (Kallitsounaki & Williams, 2023). It is also possible that interacting through screens, where social demands are reduced and communication can be more controlled, may facilitate autistic individuals’ engagement with online communities (George & Stokes, 2018).

Is the shift to screen-mediated communication limiting exposure to norms and social cues, potentially creating ‘alchemists’ whose rigid, community-driven, but disembodied worldviews somehow create identity confusion around sex and gender? It is a possibility we should consider, especially as the debate around the cause of autism rages. Regardless of the causes of ASD, the internet’s unique environment, with its algorithm-driven echo chambers and preference for controlled, low-demand interactions, is a friendly environment for those who have it, and it may be amplifying these traits in those who do not. Either way, it appears to be reshaping identity and cognition in the youngest generation (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2014).

Escaping the Algorithm, Rediscovering the Human

The alchemist’s vision—a world where human connection could be distilled into data points—has become our reality, but it has come at a terrible cost. The algorithm, for all its predictive power, flattens the messy, vibrant complexity of face-to-face human relationships into a curated feed of likes, swipes, and notifications. Without the delicate social dance through which we understand who we are in relation to other people and the world, there is no opportunity for settling into the comfort of self-acceptance. We are condemned to wander the endless horizons of the infinite and formless self. The digital alchemy we imbibe every day impedes identity formation — because identity isn’t a set of characteristics we choose, but rather emerges through experience, and with integration into the real world, made up of flesh-and-blood people striving to live together.

As for love — that elusive thing the alchemist wanted so desperately to decipher — even he, I think, would admit that the squeeze of a hand, the scent of your loved one’s hair, the pleasure at the sound of their voice are things that no algorithm, no matter how sophisticated, can replicate.

Nancy McDermott is the Director of Genspect USA, author of The Problem with Parenting (2020) and, once upon a time, and former Cyberian.

Genspect publishes a variety of authors with different perspectives. Any opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect Genspect’s official position. For more on Genspect, visit our FAQs.