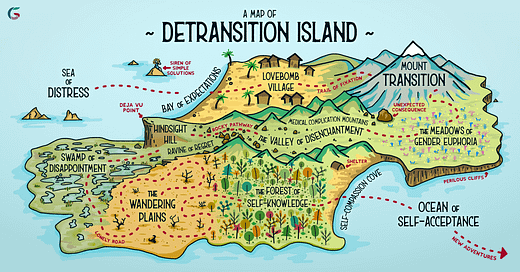

Even though it is probably the most important aspect of the new trans phenomenon, little is known about the process people go through on the way to detransition. By listening to detransitioners, we learn about the mistakes that were made; the opportunities lost; the sliding-door-decisions that were chosen. Through my practice as a psychotherapist who works with detransitioners, I’ve noticed that, although the experience can be vastly different, there can be a common path to detransition. As Angus Fox says, it doesn’t repeat but it always rhymes.

Each stage of this process can last weeks, months or years, and we don’t know how many people stay stuck at any stage. However, it can be helpful to see the arc of detransition outlined within a framework. We hope that this arc will provide a way forward for anyone who is lost in transition and that this may well give heart to anyone who is in the midst of distress and can’t quite see a way out. Detransition might be heart-wrenching, harrowing and horrible, but it also offers a new way of being, and a way to emerge from the chrysalis as a more focused and authentic person, bloodied but unbowed, and determined never to feel so fragile again.

Stage 1: Distress

You turn to the internet for distraction from the pain; you ask some questions and you find some company. It relieves your pain to find other strung-out souls who feel as weird as you do, and are seeking companionship.

The first stage of the process involves the person being vulnerable in some manner, and wishing to transition as a way to relieve their mental pain. The level of distress the individual is feeling can vary. Many detransitioners report that they felt lost, lonely, mixed up and isolated. Indeed, a therapeutic understanding of all mental health challenges can be framed within the very basic survival instinct to avoid pain and pursue pleasure. The alcoholic is motivated to avoid immediate mental pain by having a couple of drinks to take the edge off their stressed mind; the anorexic avoids pain by losing some weight and feeling a short-term charge of satisfaction that they are in control of things. Similarly, the gender-dysphoric individual wishes to escape by becoming a different person, and feels a heady charge of satisfaction every time they believe they are making in-roads in this endeavour.

Stage 2: Hope

Like Chekhov’s Three Sisters pining for Moscow, you can literally spend years pining for your new identity, and become utterly absorbed in dreaming about your imagined future self. Tending to this new identity like an award-winning gardener tends to a Bonsai tree, you disregard your real life in favour of spending thousands of hours watching YouTube videos and other social media, encouraging you to fall into reveries about a fabulous future life that promises to rid you of all your pain, uncertainty and self-loathing.

The very concept of gender identity ideology gives a ray of hope to the distressed person: detransitioners learn that, in hindsight, this hope was false. The idea that a distressed person can become a different person, with an entirely new identity, name, pronouns and body, is so incredibly alluring that it can light a spark of hope that lasts for years.

Stage 3: Belonging

The relief can be overwhelming. Finally, there is a place for you; finally, people want to hear from you; finally, people laugh at your jokes; finally, people get you! If you’re in school, you might bask in the glow of positive attention. You feel edgy and interesting; frightened but brave. It’s a heady feeling and one that isn’t easily matched. This sense of belonging can bring with it a sense of self-importance, and this stage can bring a sudden interest in politics. This may be accompanied by a powerful feeling that you ARE the Zeitgeist, and that your very being can help bring change to society – for example, by getting the rules about toilets or changing rooms or sports changed in your school. You may begin to feel contempt for whoever you believe doesn’t understand what’s going on.

When the person joins the LGBTQ+ community, in whatever guise – whether online or in person – they can feel a sense of belonging that they have never experienced before. Often, old friends are dumped at this point, and the new identity and new friends become everything. The LGBTQ+ community becomes the individual’s whole life, and nothing else matters. It is at this stage that parents often feel as though their child has been taken away by a very intense cult.

Stage 4: Euphoria

You feel invincible, as though you finally have your life sorted. You know things that others don’t, and you are taking charge of your life so that you will one day look exactly as you wish. You feel strong, clever, and insightful; having often felt timid and indecisive, you may newly feel very proud of your ability to make decisions.

Gender euphoria is the other side of the coin of gender dysphoria. It often happens roughly when medical transition begins, and is very similar to the charge of power the anorexic feels when they first discover that they are Very Good at Dieting. This feeling of intense excitement and happiness can feel brittle, heavily defended, and almost aggressive to live with. Reminiscent of feeling high from drugs, there is a wild intensity involved that can feel very disorientating for whoever lives with or loves the gender euphoric person.

Stage 5: Expectation

Until now, you had been looking forward to your future life in an almost dream-like manner – everything was going to be fabulous once you transitioned. Then, when you begin medical transition, your dreams turn to more concrete expectations, and everything can become quite specific and detailed. You might feel a sense of intense frustration at the tedious details involved with hormones and surgery. You might feel furious when things don’t go your way or when proposed medical interventions don’t go exactly as planned. Frustration isn’t really part of this dream, and so you might feel a sense of panic that manifests as rage when things go wrong, as they often do.

Irritability can come to the fore at this stage. The pre-detransitioner often feels nobody understands how important certain details are. You are feeling an impending sense of reality kicking in, and experiencing significant stress about the situation. The sudden realisation hits: while dreams are all very well, turning them into reality is sometimes impossible. The feelings of panic can be suppressed by an outward show of belligerent confidence and anger towards anyone who isn’t in total agreement. The pre-detransitioner fears making a mistake, and feels burdened by the weight of hope and expectation.

Stage 6: Disappointment

You may vacillate wildly from one extreme to another. Genital surgery is fraught and complicated, and your sweet and pleasant dreams from earlier stages are beginning to seem a bit foolish. You might hide your disappointment with aggression and can find yourself having many more fights than usual. The feelings of disappointment can hit anytime: when you look in the mirror; when you’re walking down the street; when you’re looking at a photo of yourself. Often, looks can become an even bigger focus in your life, and everything can feel utterly exhausting.

This is a crucial stage in the process of detransition, and how it is managed is critical. Very often, medication and surgical interventions bring about disappointment. The transwoman’s breasts might not grow as expected; the transman’s mastectomy is seldom perfect. Complications ensue, and the pre-detransitioner doesn’t know whether to pretend that everything is just brilliant, or start bawling that things are Going All Wrong. The more love and acceptance that can be provided with during this stage, the better.

Stage 7: Lost in transition

The lost years can continue for what seems like a lifetime. This is when you have moments of deep distress about your medical transition, but believe that there is nothing you can do about this. The thought sometimes occurs to you that, with the right support, you could perhaps choose another path; but mostly you pretend to yourself that there is really nothing you can do. You may turn to drink or drugs to dull the pain and try to seek escape from the reality of life.

Over the years working as a psychotherapist, I have often worked with people with addiction, eating disorders and depression. There almost always comes a stage, just when things are going well in the process of recovery, that the client comes in with a devastating realisation about just how damaging and needless the “lost years” were. Sometimes hysterical and other times tearful, people in this situation can be high-maintenance and difficult to be around, as they continuously seek external validation from whoever is in the vicinity. Often, these years create the most difficulties for a person: this is when most people cause most hurt. It is as yet unknown whether these lost years can be shortened, or if this is simply a gruelling process of understanding that needs to be experienced.

Stage 8: Regret

We feel very fragile when we abandon our faith; rudderless and empty inside, it is all too easy to believe there is nothing left to live for. You might at this point abandon gender ideology and realise that you have never transitioned to become another person: you are still the same person, but you look different. You might feel incredibly and justifiably angry at the LGBTQ+ community, viewing them as snake-oil salesmen – or worse.

It takes a certain type of person to be courageous enough to face the monster under the bed and admit – either to themselves or to others – that they regret their decision. Most people assimilate these feelings, considering them to be necessary learning points that made them the person they have become, and so don’t regret anything. Others might regret certain aspects of their medical transition: they might regret going to that specific surgeon, or regret not seeking better therapy prior to transition. Some people skip this stage and choose to never regret their life experiences.

In this world of relentless positivity, we often shun regret and view it as a negative experience. Yet regret has an evolutionary function: it is evolutionarily advantageous for a person to learn from previous mistakes so as to avoid future, related mistakes. Although psychological research indicates that people tend to view regret to be distressing, it is worth remarking that regret is actually rated as a “positive” emotional experience. We would all be better off if we understood that a sense of regret teaches us a cautionary tale: it paves the way for a better future, rooted in better choices, and can bring about increased forethought, awareness, and wisdom.

Suicide, however, is a serious threat at this point, and loved ones might need to be very gentle and caring during this difficult time (whilst still maintaining their carefully assembled boundaries). In his seminal work on suicide, the psychiatrist Karl Menninger said that suicide requires the wish to kill, the wish to be killed, and the wish to die. The utter loneliness that is inherent in a suicidal mindset can be penetrated, but with difficulty. This is a time for compassion, gentleness and tenderness. It is terrifying time for everyone.

Stage 9: Anger

You might feel profoundly angry that you were exploited and mistreated at your most vulnerable time in life. You become aware that there is no change in the material realities of your internal biology: while the external aspect of your body has altered, your internal workings are still the same. It is as this point that you need to access your inner hero so you can finally begin the long road of recovery.

Anger is an energy. It can propel a person to action; and it is often anger that can be the driving force that brings about detransition. The anger can be directed at the medical professionals who didn’t provide appropriate treatment – and this is right and proper. This anger can be dangerous, however, and loved ones might notice that anger can become perilously self-directed.

Perhaps the most productive way to tackle this anger is to become angry at the correct target. Over 2000 years ago, Aristotle told us that “Anybody can become angry, that is easy; but to be angry with the right person, and to the right degree, and at the right time, and for the right purpose, and in the right way, that is not within everybody’s power, that is not easy.”

Stage 10: Detransition

There is another arc: the process that follows the decision to detransition. With that, some profound feelings are unearthed – and with the right support, you can come to a place of self-acceptance and self-compassion. Accepting your biological sex and allowing yourself to let go of the obsession with identity, labels and categories can be very liberating. A sense of self-compassion towards your body can also be a profoundly rewarding experience. Getting older brings with it many regrets and many shocking experiences; however, it also brings a mellowness that is unexpected and incredibly comforting. Hang in there: it gets better. As the detransitioned woman Sinéad Watson says, “You are not broken.”

Detransition means to stop the process of transition. This means different things to different people. For some, it is enough to stop putting diesel into the petrol tank; for others, it is important to revert back to presenting as their biological sex. Some people become anti-medication; others are determined to do whatever it takes for them to resume the life they believe they should have had, had gender ideology not caught their eye. Many detransitioners who I have worked with report that they simply stopped administering the medication to themselves: suddenly, it all seemed like hard work and they just decided to take a break. Then they never started again.

By the time the person has come to detransition, they are often left with punctured hopes and feelings of deep rage and disappointment. Nothing is simple about detransition. It is not by any means the end of the road; rather, it is the beginning of a new road that has its own arc. Hopefully, and with the right help and support, this leads to self-acceptance and self-compassion. The individual might begin to find a place that they can feel at home with themselves. In the poem, The Prodigal, the poet Elizabeth Bishop describes how a suffering person can go to terrible places before finally making the decision to try to recover: “But it took him a long time / finally to make up his mind to go home.” Let’s hope that we all have the chance to go home one day.

This article was first published at Genspect.org on 10th March 2022.