I grew up learning about censorship. It bored me to tears at the time; however, I couldn’t help but learn about it. It was on the nine o’clock news every single night.

My first introduction to politics was that there were IRA (Irish Republican Army) men in the North of Ireland who were slowly starving themselves to death in prison. It was 1981, and it was a shocking, harrowing time. The graffiti on the walls on my way to school said in huge capital letters “END THE H BLOCKS”. As a seven-year-old, I had no real idea what this meant, but I knew it had something to do with the pictures of the emaciated men on TV.

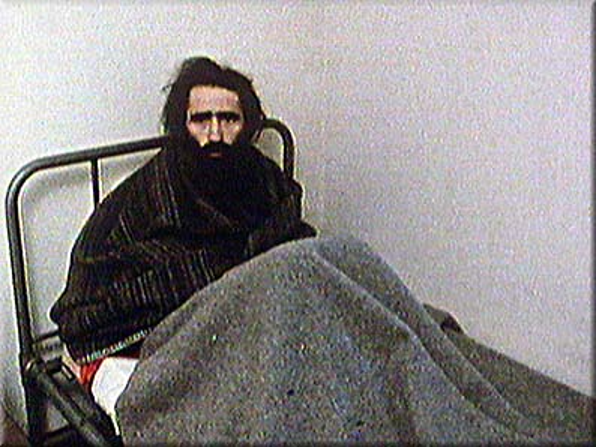

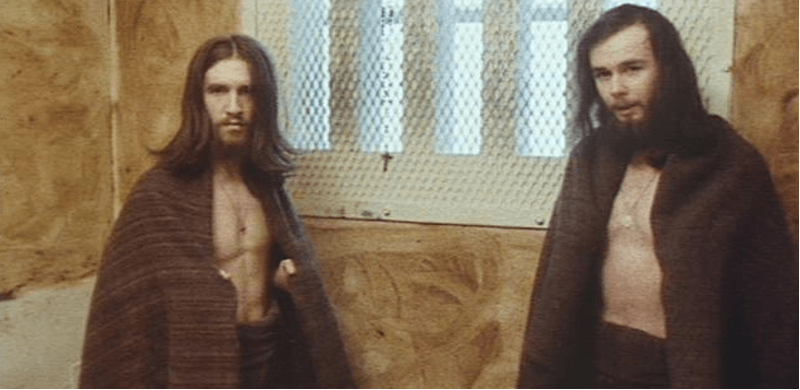

The images of the ‘dirty protest’ that the IRA prisoners had attempted before the hunger strikes were even more horrifying to my seven-year-old self. The prison authorities had removed all furniture in the cells except for mattresses and blankets, after a riot that was sparked by their violence against a prisoner. The political prisoners responded by refusing to leave their cells: they lived naked, and cold, and wore only blankets. This meant they couldn’t slop out, which began the dirty protest, where they smeared their faeces on the walls.

What does this have to do with gender, you might wonder? Well, in this piece I want to highlight the insidious impact of censorship. Open dialogue is the lynchpin of civilised society, and no good comes from suppressing people’s voices. When we disagree, we need to speak about it. When a person says hateful things, we need to speak about that, too. Thoughtful discussion is the best way to deal with conflict.

Censorship – in the form of Section 31 – prevented open dialogue during the Troubles in Ireland. The IRA was censored, as was its political wing, Sinn Féin. The censorship became so extreme that the voices of Sinn Féin representatives could not be broadcast on national television, and (in a move which now seems quite bizarre to many) were dubbed instead. Not only that, but every attempt to ask questions was generally silenced with a reproving look: you might be siding with the violent madmen. So, many people, including me, found it incredibly difficult to figure out what the hell was going on.

How the IRA had reached this point is a long, complicated story, reignited in the 1960s when peaceful protests for civil rights (inspired by civil rights movements all over the world) were violently suppressed by the Northern Irish police. By the mid-1970s, the IRA prisoners wanted to be recognised as political prisoners engaged in political struggle – and free to wear their own clothes, rather than prison uniforms. The British government refused.

When the British government didn’t yield, the IRA escalated matters further with the hunger strikes. In 1980, the first hunger strike began, with five prisoners refusing all food. On 18 December 1980, after 53 days of hunger strikes, and one man slipping in and out of coma, the British government appeared to concede: the hunger strike was called off. It soon became clear that the British government had not in fact ceded ground, and the hunger strikes began again in earnest in March 1981.

Between March and October 1981, ten men died (aged between 23 and 29 years old), one after another, and others suffered terrible long-term injuries, all in a bid to be recognised as political prisoners. A glimpse into this world was offered to me as a child when I was told how there was food at all times in the prison cell with the hunger striker. Breakfast would be served in the cell in the morning, to be replaced by lunch, and then the last meal of the day, which would be left in the cell overnight. The intransigence on both sides melted my mind.

The hunger strikes were billed as a campaign of emotional blackmail and, eventually, the strike was declared a failure. Margaret Thatcher, the British prime minister during the hunger strikes, famously declared “crime is crime is crime”, denying the very notion of the political prisoner. The IRA concluded she would never yield, and the strike was called off after ten prisoners had starved themselves to death. Three days later, the British government announced a number of changes in prison policy, including that from then on all paramilitary prisoners would be allowed to wear their own clothes.

It was a bitter conflict.

However, the strikes brought the attention of the world media to the troubles in the North of Ireland. Bobby Sands, the most famous hunger striker, was elected to the British parliament while in jail, and became a folk hero, with his funeral attended by 100,000 people.

This was all very complicated for my seven-year-old self – but the pictures weren’t complicated. Something terrible was happening.

As a child growing up and coming to consciousness, censorship just didn’t make sense to me; and it still doesn’t. Why not speak to the IRA or Sinn Féin? I thought; surely this would bring about peace sooner? The IRA continued to escalate their campaign of violence and stories of men, women and children being blown to pieces by bomb blasts became a regular fixture on the news in the 1980s.

During those terrible years, the British government said again and again that they would never talk to the IRA. Margaret Thatcher was famously intransigent in her determination to starve the IRA of ‘the oxygen of publicity’. When a proposed peace deal, the Anglo-Irish agreement, came about in 1985, Ian Paisley, leader of the anti-Sinn Féin Unionists, famously said ‘never, never, never, never’ should the north of Ireland be influenced in any way by the south of Ireland. It felt like nobody would ever agree on anything.

It also felt like everybody in Ireland was an expert on censorship, no-platforming and guilt by association. Because back then it wasn’t enough to condemn the violence: you had to condemn everyone with even the most tenuous connection to it.

I went to a Gaelscoil (an Irish-speaking school) in Dublin: madly enough, this was generally considered a ‘Republican’ type of activity, so I would often hear passing dismissive references to Gaelscoileanna and the IRA. It was an early introduction to the farcical nature of a life lived under the spectre of guilt by association: the accusations were not of complicity, but of ‘dirt’ rubbing from one person’s shoulders onto the next. It wasn’t criminality that was alleged but proximity. This is strikingly familiar to anyone who has dared to speak up about gender politics today.

Just like today, the situation was incredibly complicated, and only a tiny number of experts would dare to comment. The vast majority stayed well away, understandably afraid they would make a mistake and attract the attention of the angry mob. Also reminiscent of today, the only other people who spoke out were those personally impacted by the situation: the mothers; the families. It felt like nobody really understood.

We are now privileged with peace: riots are generally played out online, not in real life. But there’s an eery similarity between today’s language policing over trans issues and the intense monitoring of speech during the Troubles. In both cases, people are divided immediately on the basis of the words they use.

Just like today, terminology was all-consuming. Did you say Northern Ireland, marking you out as a Unionist, or the Six Counties, marking you out as a Nationalist? Derry or Londonderry? The Free State or Southern Ireland? An old joke tells of a man in need who flags down a passing car. ‘Are you Catholic or Protestant?’ the driver asks, warily, trying to judge whether or not to help. ‘Neither,’ says the man in need: ‘I’m Jewish.’ After a pause, the driver responds: ‘Yes, but are you a Catholic Jew, or a Protestant Jew?’

The divide became inescapable; behaviour and habits were similarly polarised.

The judgement was quick and brutal, as the no-platforming culture wielded its dreadful cudgel. This led to a chilling effect: most people remained silent, feeling ill-informed about the complexities of the issues, and frightened of the violent sense of outrage whenever someone was deemed to be insufficiently sensitive.

Try to imagine my own sense of horror when I found out, as we all did, that the British government had in fact been talking to the IRA all along. With the shocking death toll – and the toll on the mental health of everybody in the North – both British and Irish authorities had fully understood the critical need for discussion, despite their public complacency. To this day, many are unaware just how many bombings took place.

The truth was that the authorities were lying: secret talks took place all through the 1980s and 1990s. So all the censorship and no-platforming was all for show: posturing, and playing to the crowd. It left me with a lifelong aversion to censorship, no-platforming and guilt by association.

I’m not the only one who learnt bitter lessons from all this. This tweet by the Irish psychotherapist Beth Wallace is reflective of many people’s thoughts about all this:

Many in Ireland have an equally in-depth understanding of the iniquitous impact of the silencing of debate. Just recently, I was engaged in a community activity where my colleagues included an ex-IRA hunger striker; a very religious, pro-life Catholic; and a knit-your-own-yoghurt, vegan hippie. None of us agree politically in certain contexts, and yet we got along just fine. In fact, we had great craic. And we got our project over the line without heated debates about our ideological differences.

This is completely normal in Ireland. Although some younger and less informed Irish people are currently arguing for censorship and no-platforming, it is generally regarded with a wary suspicion borne from bitter experience – and it’s seen as a matter of regret that a lesson so painfully learned has not been sufficiently imparted to a younger generation.

This is why, when I first became engaged in the gender debate, I was astonished to see the hashtag #NoDebate. Surely, I thought, all right-thinking people had moved beyond suppression of debate?

In many ways, no-platforming and censorship come from a place of privilege. People who are desperate will generally let anyone help them: if you get mugged and someone comes to your rescue, you’re unlikely to stop them mid-rescue and ask them to give a detailed analysis of their politics.

I also believe that censorship suggests a certain amount of arrogance. Who are we to know where we are in the curve of history? It is laughably unlikely that we have the full facts at our disposal. None of us knows the best way for society to move forward, which is why we have to listen to people with whom we disagree. Shutting down those who are engaged in civil and mature debate, simply because of their apparent wrong-think in other contexts, deprives us of the opportunity to hear the many different views on a given subject.

Seeking common ground is perhaps the only way forward when we disagree. Thousands of people died in the Troubles between the 1960s and the 1990s. Finally, in 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed and peace slowly stuttered into the island of Ireland. It has not been perfect. In fact, there were dreadful acts of violence after the agreement was signed.

To this day, most people are annoyed about various aspects of the agreement: but bombs aren’t on the nine o’clock news anymore. Most Irish adults over forty have learnt that censorship can lead to violence: that silenced people will demand attention one way or another, and will keep upping the ante until they’re heard. Civilised discussion and open dialogue are essential if we are to find a way forward.

This is why we have decided that Genspect will speak with anybody.

For example, some campaigners against paediatric transition oppose gay marriage. Immediately, the allegation is levelled: if Genspect talks to people who are against gay marriage, Genspect is itself against gay marriage. But we need as many voices as possible arguing for better healthcare for young people, and they don’t need to agree on gay marriage. Or abortion. Or climate policy, Brexit, veganism, or star signs. Placing such a condition upon the conversation weakens us. Interestingly, those in favour of paediatric transition rarely place such conditions on their allies, maybe explaining why they’ve been so successful until recently.

The most powerful examples of collaboration frequently arise precisely because people set aside their differences. One Genspecter, Angus Fox, only became aware of the gender issue because he watched a conference where a radical separatist lesbian was appearing alongside a member of the conservative Heritage Foundation. ‘It was like seeing a geisha on an oil rig,’ he remarked. The stark contrast between the two – the conservative’s starched side-parting versus the lesbian’s punky tufts – showed how certain, and how passionate, both must have been.

So, our policy is that everybody is welcome to engage. When we disagree, we are forthright and transparent; however, we also endeavour to find common ground, hopefully moving towards a better society. And when we have improved the healthcare afforded to young people questioning their gender, we can, if necessary, part company: for now, other battles can wait.

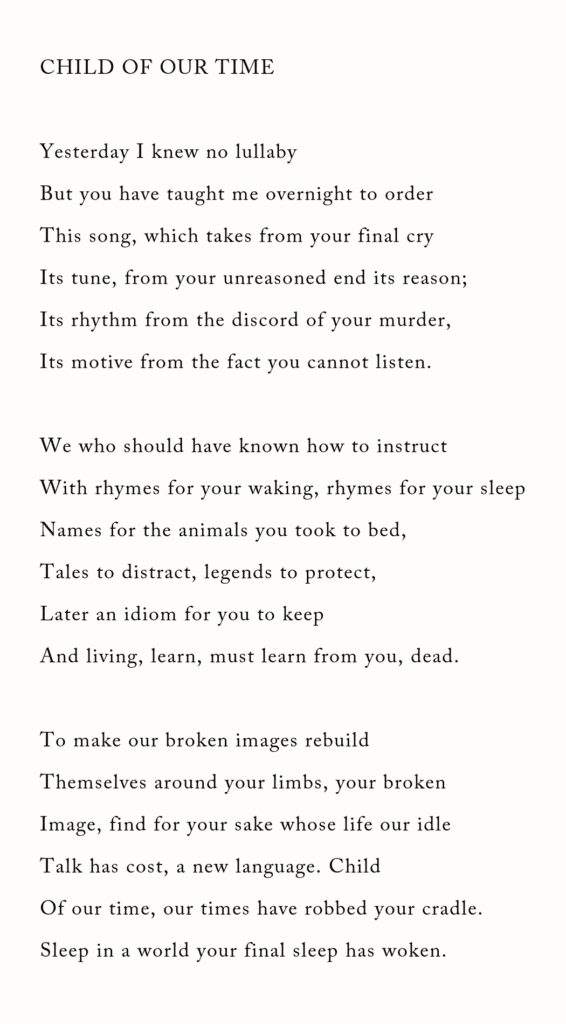

It is for this reason that when somebody tries to shame me for interacting with the “wrong people”, I think of the poem “Child of our Time” by the Irish poet Eavan Boland. Boland wrote this poem after she saw a picture of a fireman lifting a dead child from the remains of the Dublin bombings in 1974. She realised that we simply had to find a better way to communicate; that we needed to find a new language.

It might have taken us many years, but in Ireland, we finally did find a way to communicate; a way to agree to disagree. As Boland told us, these tragedies are pointless and horrific. All we can do is remove ourselves from idle talk and instead learn to do better. “We who should have known how to instruct …must learn from you, dead….Child of our time, our times have robbed your cradle. Sleep in a world your final sleep has woken.”

There is no other option.