Understanding ‘Gender Affirmation’ as a Patent Medicine Show

An historical parallel to the broken ethics of ‘gender medicine’ is becoming relevant in our time.

At the founding of the American nation, medicine was an individual pursuit. Colonists used ‘proprietaries’ made from herbs and sold as medicine. Doctors were rare, and their profession was, as yet, hardly professional. Distrust of ‘scientific’ medical knowledge was understandably common when physicians were still using lancets to bleed patients. Self-diagnosis and self-cure were widely preferred to arcane Latin terminology.

Beginning in 1796, when Samuel Lee Jr. patented his first ‘nostrum’, a fledgling United States government was happy to sell anyone the right to mix their own medicinal recipe and sell it to the masses. Following independence, these evolved into one of the first major domestic industries, with ‘patent medicines’ accounting for half the advertiser revenue of American newspapers for most of the 19th century.

Unsurprisingly, ‘editors adopted a tacit policy of supporting the medicine industry, as they (or their publishers) were loath to criticise their most important source of income,’ Ann Anderson writes in Snake Oil, Hustlers, and Hambones. ‘As a result, the public was slow to learn about the dangers posed by many of the formulas.’

Many ‘cures’ contained poisons. Chloroform, digitalis (foxglove), kerosene, strychnine, turpentine, and arsenic were often mixed with opium and its derivatives, such as morphine and heroin, along with cannabis, herbs, emetics, and purgatives, all suspended in alcohol. Patent medicine manufacturers insisted that high alcohol content was vital to their formulations. In reality, of course, they wanted repeat customers buying their ‘cures’ to chase a chemical high.

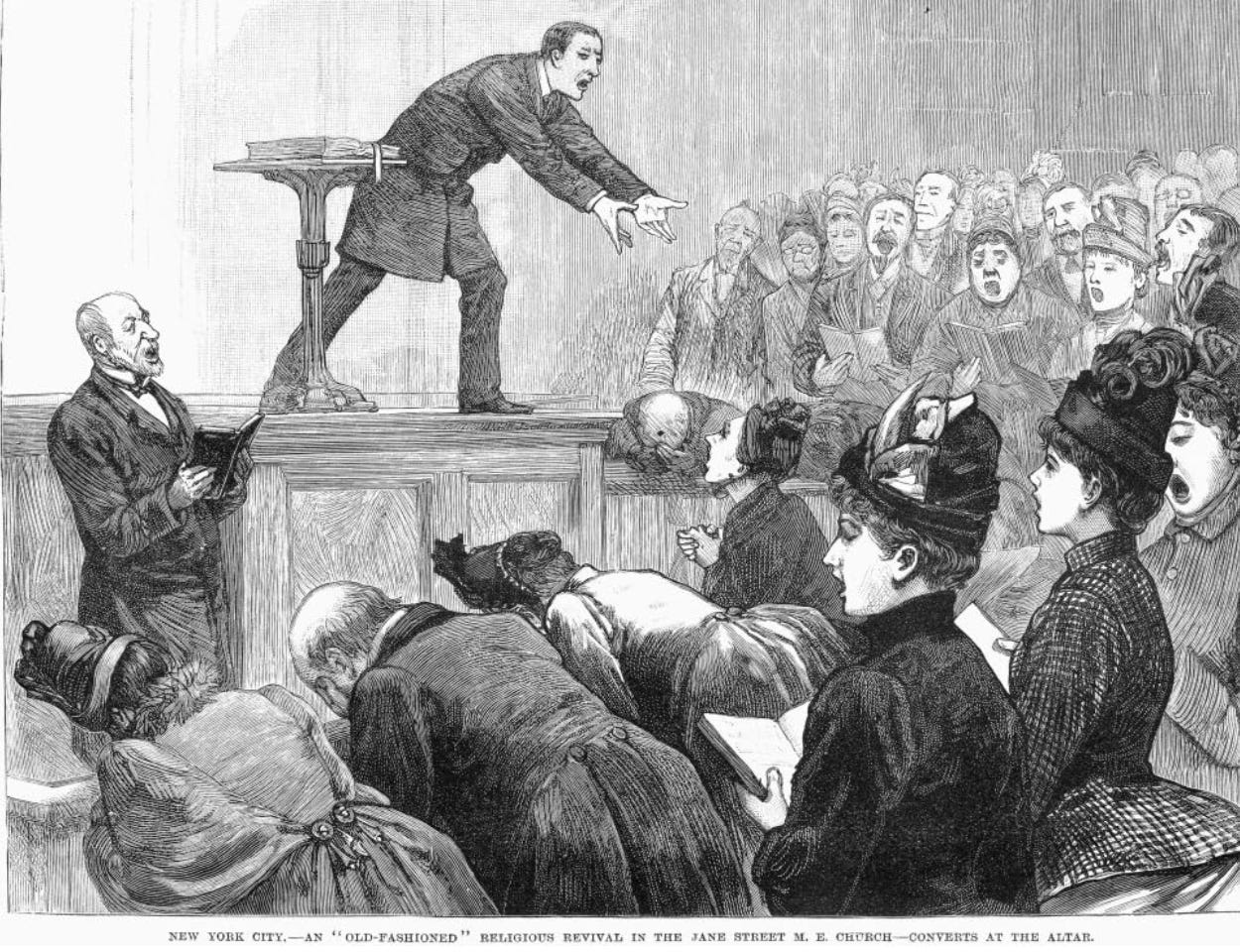

History preferring irony, this effect was most visible during the American Temperance Movement. Travelling ‘Temperance plays’ would offer free samples of their ‘cure’ to the teetotallers as they entered the venue. Callithumpian bands would play outside, while sermons against demon rum and heavenly singing were inside. With everyone having a good time thanks to the chemical boost, they would find more of the ‘cure’ for sale before they reached the exits.

‘For a time, more alcohol was consumed in the form of patent medicines than in liquor,’ Anderson writes. P.T. Barnum and William ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody are just two famous showmen of the period who profited from patent medicines. ‘Anything entertaining or attention-getting’ — magic tricks, ventriloquism, melodramas, phrenology demonstrations, ghost stories, fairy tales, morality plays, the very first portable electric generators and lighting — ‘made its way into the medicine show platform.’

Negative consequences were, of course, common. For the travelling salesman of patent medicine, the trick was to pull up stakes and leave town before the money stopped and the complaints started. One could always rebrand with the same basic formula and come around again, later, since no one was monitoring or regulating the manufacturers.

Whereas the patent medicine show had largely faded by 1920, Prohibition gave it new life as Americans got drunk on more dangerous concoctions than liquor. Newspapers, which now had far bigger client accounts than patent medicine hucksters, began to do their job.

The ‘Jake Leg’ Blues

In perhaps the most famous example, during 1930, The Oklahoman reported an outbreak of paralysis around Oklahoma City. Similar outbreaks were happening across Kansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and the West Coast. Thousands of people, mostly men, mostly black, suffered from ‘jake leg,’ a spinal malady resulting in an inability to walk normally

Oklahoma doctors blamed the epidemic on ‘poison whiskey,’ a concoction made with Jamaican ginger root that was 70 to 80 percent grain alcohol. Chemical analysis revealed the following year that the Jamaican ginger root was tainted with tri-ortho-cresyl phosphate, or TOCP, which can cause permanent neuropathy when consumed.

In the meantime, the terms ‘jake leg,’ ‘jake foot,’ ‘jake walk,’ ‘jake wobblies,’ and ‘jakeitis’ entered the lexicon of emergent American popular culture, with the most famous example being Jake Leg Blues by the Mississippi Sheiks.When you see him coming, I am going to tell you,

If you sell him jake, you’d better give him a crutch too,

Oh well, it’s here he comes, I mean to tell you, here he comes,

He’s got those jake limber leg blues, oh step on it.

As news editors began to cover patent medicine poisonings, a new public awareness of the harms increased demand for regulation. Starting with the creation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1906, federal officials increasingly reined in the abuses of the patent medicine industry using the scientific method and an emerging technological bureaucracy. Yet patent medicines were still quite popular when they were not poisonous.

Hadacol, America’s last great patent medicine brand, was a case in point. Dudley J. LeBlanc, a Louisiana Cajun, ‘transformed the Bible Belt into the Hadacol belt’ and made $24 million per year, a huge fortune in 1951. Hadacol contained B vitamins and 12 percent alcohol. Harmless, it was often sold by the shot glass or mixed into cocktails. What made LeBlanc an innovator, though, was his solicitation of testimonials from consumers. Hadacol users claimed it had cured everything under the sun, including cancer. A team of employees would record the customers, talk to neighbours and relatives, and scrupulously document these ‘cures.’

The testimonials ‘made good advertising copy, and were also a clever way to get around governmental restrictions on fraudulent claims,’ Anderson writes. FDA pressure eventually succeeded in forcing LeBlanc to stop making specific medical claims, however.

This history might interest Justice Sonia Sotomayor, whose disappointing dissent from the US Supreme Court’s Skrmetti decision includes similar testimonials from parents of ‘trans kids’ who are convinced that chemical castration has been a panacea for everything that ailed their children.

Another salient point is that Hadacol marketing played on stereotypes associated with ‘hoodoo,’ an American system of folk magic that is cousin to voodoo, to sell LeBlanc’s product. Patent medicine shows always trafficked in stereotypes, playing on every trope of foreign or exotic origins. ‘Cures’ for ‘female trouble’ invoked the Old Maid, the Suffragette, and the Nagging Wife.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which spawned many stereotypes of slavery, was produced everywhere on stage to sell patent medicine before the American Civil War. In these shows, ‘men with smudged faces and inside-out clothing, reminiscent of chimney sweeps and coal miners, were a precursor to the blackface minstrel clown,’ Anderson writes.

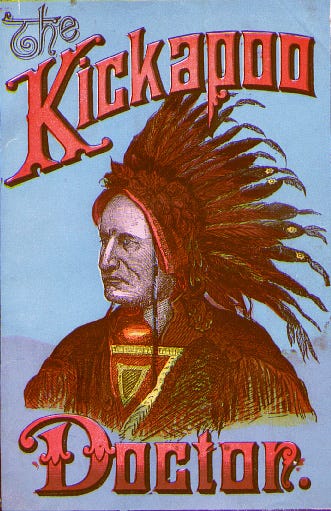

Noble Savage Cures

But the most common, and by far the most successful stereotype used to sell patent medicines, was ‘the romantic Indian who was in perfect harmony with the environment, never got an illness he couldn’t cure, and was the physical and spiritual superior of the white man.’ This American version of the ‘noble savage’ was a common medical trope during the 19th century, for ‘sincere health practitioners as well as hucksters used the repute of Native Americans to drum up business,’ Anderson says.

I have talked to dozens of detransitioners and listened to hundreds. All of their stories are different, even when similar in some ways, with the sole exception that they all shared a false belief that they were transgender, this belief always being based on sexist stereotypes. They are victims of a swindle.

The Pedigree of Flimflam

In confidence art – the criminal art of fraud – weapons are generally avoided. Con artists are sometimes referred to as the ‘noble criminal’ because they do not force their victims to give up anything. The con artist doesn’t ‘steal,’ the mark ‘gives.’ As Rex Sorgatz writes in the Encyclopedia of Misinformation, ‘the only weapon is the story of the con itself.’ Or as the postmodernists put it, what matters most is control of ‘the narrative.’ Tell the loudest, most convincing story, and suckers will queue up to buy whatever you are selling. Stereotypes are powerful this way. They contain stories that we already want to believe.

Europeans perfected the art of the travelling medicine show centuries before American independence and many elements crossed the Atlantic to become familiar tropes. Our word ‘charlatan’ comes from the Italian ‘ciarlatano,’ ‘one who sells salves or other drugs in public places, pulls teeth and exhibits tricks of legerdemain,’ Anderson writes. Another example is ‘Mountebank,’ the Venetian term for ‘the one who jumps on a bench’ to perform tricks, sell potions, and offer open-air dentistry services.‘Zany’ comes from ‘zani,’ Italian for ‘clown.’ Many clowns worked as assistants to these potion peddlers, bringing in crowds, praising the potion-master, and recounting his many successful interventions. Jeffrey Marsh is a modern patent medicine clown; his act is over-the-top by design.

The English quack also left a legacy. His clown assistant, ‘Merry Andrew,’ recommended his master to the crowd, extolling his virtues as a sage and scholar whose cures had relieved his every health complaint. Innumerable alchemists presented themselves as the High-German Doktor or the Italian Dottore. A convincing foreign accent made nonsense seem more plausible.Today, we understand this as the ‘appeal to authority,’ a logical fallacy that recurs constantly in apologetics for ‘gender medicine.’

Justice Clarence Thomas recently examined this point in his concurring opinion on Skrmetti. Plaintiffs ‘would permit elite sentiment to distort and stifle democratic debate under the guise of scientific judgment, and would reduce judges to mere spectators … in construing our Constitution,’ Thomas wrote. ‘States are never required to substitute expert opinion for their legislative judgment, and, when the experts appear to have compromised their credibility, it makes good sense to chart a different course.’ Indeed, too many doctors and experts have beclowned themselves with the hocus-pocus wordplay of ‘gender identity’; it has transformed academia into a circus.

Finally, religious overtones were always present in the medicine show. ‘The audience was put in the role of congregation, receptive and passive,’ Anderson writes. ‘Quacks likewise had no compunctions about linking their pitches to religion.’ Faith and fraud were ‘entwined in an odd yet profitable relationship’ for most of the 19th century. Patent medicine pitches were consciously modelled on circuit-rider tent evangelism. Victims of patent medicine fraud frequently swore by their ‘cure,’ itself a result of confirmation bias

The astute reader who is familiar with the issues covered at Genspect will discern many commonalities between patent medicine fraud and gender medicine fraud, and indeed the word ‘fraud’ is about to take on a newly operative meaning in the fight against the harms of ‘gender medicine.’

As a matter of law, ‘fraud’ is an act of intentional deception or misrepresentation of facts that causes another person to give up something of value, or some legal right such as ownership, through trickery or deceit. Gender clinicians have played fast and loose for more than a decade as their numbers exploded across America. Parents have been extorted with suicide threats, patients were not told about complications, normal professionalism was abandoned. It was all predicated on the lie that human sex can be changed.

Calling It by Name

This was fraud. Detransitioners have given up some part of their health, and/or their healthy bodies, because they were lied to. In every case, an entire community told them a story they were primed to believe: that they were ‘born in the wrong body,’ that they could be ‘fixed’ with hormones and/or surgeries, that they would die unless they got to live in the perfect body.In the wake of Skrmetti, the gender industry can be forced to change its ways. Adults are free to buy plastic surgery in America. They are free to swallow, inject, or apply poison if they want to. But these things must be marketed honestly: the weed killer is clearly marked as poison, while voluntary cosmetic procedures are not covered by most health insurance because they are not ‘life-saving.’

Moreover, gender clinicians have allegedly taken advantage of medical coding to commit insurance fraud, including Medicaid fraud. These issues will be discussed at a 9 July workshop, to be held by the Federal Trade Commission in Washington, DC, featuring ‘doctors, medical ethicists, whistleblowers, detransitioners, and parents of detransitioners.’‘Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act gives the FTC broad authority to protect consumers from unfair or deceptive acts or practices,’ reads the press release. ‘This authority could be implicated if there is evidence that medical professionals or others omitted warnings about the risks or made false or unsupported claims about the benefits and effectiveness of gender-affirming care for minors.’

I will be in Washington to cover the event for The Distance as a reporter. As a historian, I consider ‘gender medicine’ in general – and paediatric ‘gender medicine’ in particular – to be a historical example of patent medical fraud. Sooner or later, the practitioners were bound to collide with civil and even criminal consumer protection law. History appears to be rhyming.

Genspect publishes a variety of authors with different perspectives. Any opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect Genspect’s official position. For more on Genspect, visit our FAQs.

This September, join Genspect at The Bigger Picture conference as we expose the lies, half-truths and deceptions of identity medicine.

Tickets selling fast - secure your seat now.