When a gender-nonconforming girl and a sexist society conflict, it’s not the girl who needs to change.

I was swinging on the swing set in our back yard in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania when my mother approached to offer me what could be considered gender-affirming hormones. This was 1969. I was thirteen. Mom, a physician, was still wearing her lab coat after a day at the office. I stopped swinging.

“You’re already tall,” she reminded me. I was five-eight, according to our family’s giraffe chart. Average woman’s height: five-four. “If we don’t arrest your growth, you might…”

Uh-oh. What horrors could befall me if my body continued stretching, like a tree, toward the sun?

This is a story about the dangers of treating gender nonconformity as if it were a disease. Indirectly, I hope to shed light on the modern-day harms of treating girls with puberty blockers, testosterone, and mastectomies.

“If we don’t arrest your growth, you might not be able to find clothes to fit,” Mom continued. She said “clothes,” but I could tell she meant “a husband.”

My mother was five-ten-and-a-half. Dad was six-three. She had told me earlier that she was “almost an old maid” before she found tall-enough Dad.

In a sexist society, being taller than most men (average male height: five-nine) is a gender-nonconforming thing to do. I have intimidated many a man simply by standing up.

At thirteen, marriage was not on my mind. I had started “liking” boys, but only because my girlfriends were doing it, and “Who do you like?” seemed to require an answer. My friend Janne liked Martin, so, with thirteen-year-old logic, I liked Martin too. Martin was five-four. When standing near Martin, I tried to casually dislocate one hip.

Adrienne Rich defined compulsory heterosexuality as the cultural assumption that the only place a woman can find romantic love is with a man. Compulsory heterosexuality was so dominant in 1960s rural Pennsylvania that I had no clue how to interpret my affection for girls, nor my indifference to boys.

Being a lesbian: another gender-nonconforming thing. In a sexist society, women are supposed to put men first. Lesbians don’t.

Sports saved me, body and soul. By thirteen, I had become a summer-swimming champion and was excelling at three other sports in junior high.

Being a female athlete, especially in the sixties: another gender-nonconforming thing. Female strength, discipline, competence: none of that is “feminine.” 1

Did any of the boys, including Martin, “like” this towering, assertive athlete who had insisted on playing football with them during elementary-school recess? Not so much. Which made me even more vulnerable to Mom’s proposal.

My mother was a competitive swimmer with an impressively feminist career. I adored her. She had read about the new treatment for “excessive height in girls” in JAMA, one of many medical journals that adorned our living-room tables.

The hormones Mom offered were estrogen. Before puberty, estrogen (given in the form of birth control pills) induces a girl’s first period and stunts growth.2 After menarche, girls usually only grow about another two inches.

My older sister had not started menstruating until she was fifteen. If I continued growing for another two years, then another two inches after that, I might be…

“How tall?” I asked.

Mom showed me a Metropolitan Life Height/Weight table she had superimposed with my giraffe-chart data. Compared to the average-girl contour of gradually rising foothills, my route looked like a steep Mount Everest peak.

Mom also factored in a formula she knew to predict adult height: Double the height of a two-year-old, then add a few inches for a boy or subtract a few for a girl.3

“Worst case scenario,” she speculated, “you could be six feet tall.”

Whoa. Had such an Amazon ever been sighted in Blue Bell?

“Would I still reach five-ten or eleven?” I asked, negotiating. Basketball was already important. Mom assured me I was destined to be tall, regardless.

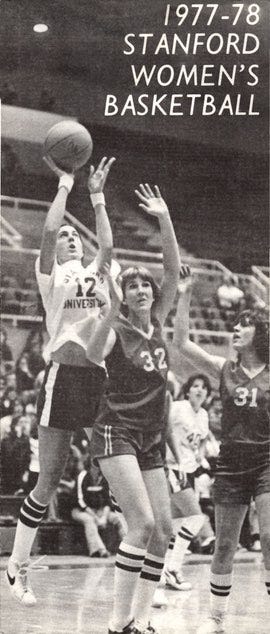

How could I foresee that I’d play basketball at Stanford and in two professional leagues in Europe and the United States? That I’d study with the great Sandra Bem, who popularized the word androgyny and explained that sex roles are bogus? That I’d use those experiences as a springboard toward a writing career focused on the empowerment of women through sports? That I’d happily marry five-foot-six-inch Katherine?

“I’ll leave the decision up to you,” Mom said. But this was my mother and my doctor. Dad was a doctor, too. The proposal delivered to the thirteen-year-old perched on the swing carried with it the full weight of parental authority, medical authority, and the latest medical research.

I took the pills. And grew to be six-two.

From this perch, it’s hard to complain about stunted growth. The estrogen was probably administered too late to make a difference, though I prefer to think my body was stubbornly unshrinkable.

Unfortunately, hormones are still prescribed for “too-tall” girls (but not boys) whose projected adult height is anywhere between five-nine and six feet. Fifty years of feminism notwithstanding, male acceptance remains so paramount that girls’ height, like girls’ feet in ancient China, is still modified to satisfy men.

Yet estrogen is not recommended as a contraceptive before puberty due to numerous side effects, including “menstrual irregularities.” In my case, I do wonder. In my forties, I suffered from fibroids, endometriosis, and endometriomas, which led to a hysterectomy and oophorectomy at 47, which triggered new side effects. Early estrogen and early hysterectomies both impact bone density. By fifty-six, I had osteoporosis.

I worry, too, about other gender non conformers: the athletic, androgynous, and/or lesbian girls who adopt trans and nonbinary identities.4 Like me at thirteen, they’re too immature to make big decisions, they’re implicitly pressured by adult authority, and they’re unable to predict the future.

Growing up female is tough enough.

When a gender-nonconforming girl and a sexist society conflict, it’s not the girl who needs to change.5

If I had been born fifty years later, I Would Have Been Trans – and would have regretted it.

Estrogen has never been approved by the U.S. FDA for growth suppression. But between 1995 and 2000 (the most recent data I could find), 33 percent of U.S. pediatric endocrinologists used estrogen to suppress growth in tall girls.

This formula and variations on it are still used, though there seems to be no validating research.

An earlier version of this story appeared in Kara Dansky’s TERF Report.

Genspect publishes a variety of authors with different perspectives. Any opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect Genspect’s official position. For more on Genspect, visit our FAQs.

I’m very wary now of pediatric endocrinologists. The hubris of monkeying with healthy, developing human bodies for strictly aesthetic effect seems antisocial, anti-science, and frankly, sexually depraved.

This story reminds me of what I recall a neighbour saying to me about her “small stature” 9-year-old daughter in the late 90s. She’d been born with hydrocephaly, but otherwise perfectly healthy. The doctor had suggested “growth hormone” administered pre-puberty. Everything in me rebelled, I asked what the negative side effects could be, I don’t recall what if any the mother shared. I cared deeply for this girl, and I urged Mom not to give her the drug, to allow her to grow unaffected by exogenous anything.

The idea was that she might not crest five feet. “Who cares?” I asked. “Why would that be worth risking her health, after all your family has been through with her hydrocephaly and shunt? Leave her alone!!”

They did. I think she topped out at 5 feet, I don’t recall. She’s a happily married mom of a little boy now.

An endocrinologist who peers at healthy children, predicts their aesthetic future requirements, and grabs his prescription pad to craft an adult body he deems appropriate is a ghoul.

It shouldn’t be part of medicine to evaluate young children through the lens of reproductive or sexual aesthetics, and suggest exogenous chemical mutations that lead to loss of function and diminished health.

They should stick to the pancreas, I say. Diabetes is where these guys are useful. Otherwise, they terrify me.

This is a piece that touches me, personally, in many ways.

“…a sexist society…” This ideological phenomenon is often described as misogyny. But the word “sexist” is somehow more directly to the point, and cuts through the many arguments that gender-allies might use to confuse and gaslight—some of the same nonsense arguments they have heard that confused them in the first place.

As this messing with kids’ natural development deeply disturbs me, your essay also brings to mind a not-so-good-enough mothering experience of my own, perhaps because of this being the morning after Mother’s Day: my personal experience of discomfort when my daughter started to outgrow me.

I remember how disconcerting it was to have my little girl stop looking and being little. I had unconsciously expected her to end up petite, like me. I had not prepared for her to change so much and begin to surpass my 5’2” frame.

Something inside of me was clearly resistant to a reality I had not imagined, seeing my daughter from a new perspective I had never considered. Psychologically, it felt as if she was somehow leaving me. I resisted. Not verbally but mentally and silently. I remember feeling intense separation anxiety.

It took me a while to get used to her growing to 5’5”. Although that’s pretty standard for a female, at that time it was quite jarring to me. Similar to your mother’s desire to control your body, I, too, (subconsciously) wished the same.

It was a phase in my parenting I’ve often looked back on with some concern. I’m aware my reaction was unhelpful and unhealthy, at the very least. With this piece, you’ve helped me understand why. I was reacting from my own internalized, sexism anxiety, and passed it down to her as one does a cherished heirloom.

I noticed that throughout high school, and even to this day, my daughter slouches a little. I’ve not realized until now that it may have to do with an unconscious attempt to stay closer to my height level, as if giving me what I wanted, perhaps as a response to my anxiety during that time in our lives when I unintentionally communicated this.

Perhaps by sharing this realization with her I can help her reclaim her right to her height, her body, and she can honor herself that little bit more—and give back a hand-me-down that she does not need and that I do not want her to keep.